Wildfires

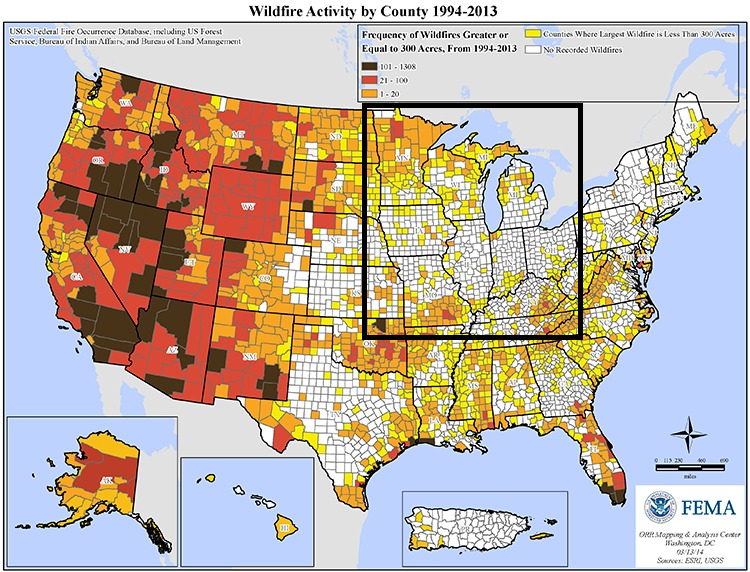

Wildland fires have been a natural component of the earth-atmosphere system for thousands of years, and are an important natural process in maintaining the natural landscape of the Midwest. Wildland fires benefit ecosystems by reducing unwanted, harmful forms of vegetation and animals, while promoting the health of vegetation and animals that are naturally a part of that community. Humanity has increased the number of wildland fires since record keeping began, with current records indicating that humans cause 9 out of 10 fires directly or indirectly (National Interagency Fire Center 2015). Debris burning, campfires, arson, discarded smoking products, sparks from equipment, or power lines that experience a surge in electricity and release that surge as an arc or power flash (similar to static electricity build-up and the resulting spark) are several examples of how humans can cause wildland fires. This page describes wildland fires – where, how, and why they form - and what you can do to be prepared in case a wildland fire threatens your home or community. Wildland wildfires in the Midwest (see map below) are most frequent in counties with forested land.

Midwest Fires by the Numbers: 2002-2014

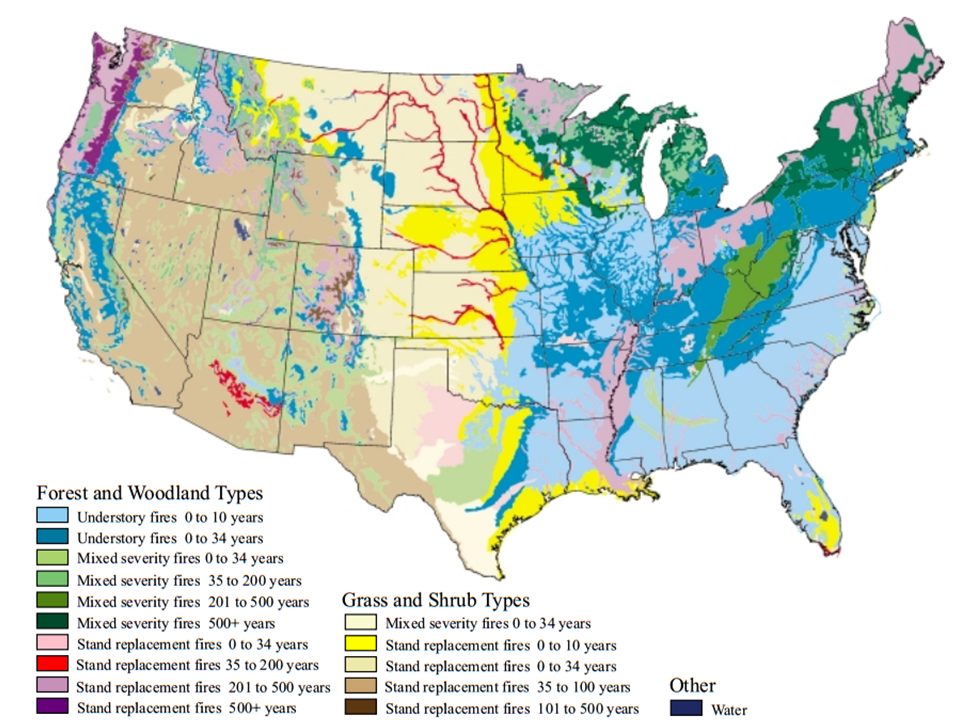

Much of the United States is classified as fire-dependent ecosystems. Within the Midwest the fire regime, which is the general time-frame in which wildland fires occur naturally in a given ecosystem over time, is primarily 0-34 years. A fire regime is determined by characteristics such as fire frequency, intensity, severity, seasonality, size of burn, fire spread pattern, and pattern and distribution of burn. Thus, while wildland fires in the Midwest are not the size of those out West, they are common. In fact, in states such as California that are prone to wildland fires, the fire regime is the same as the Midwest (0-34 years).

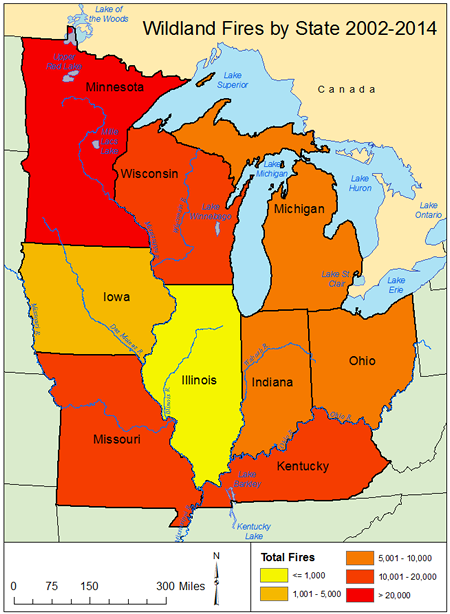

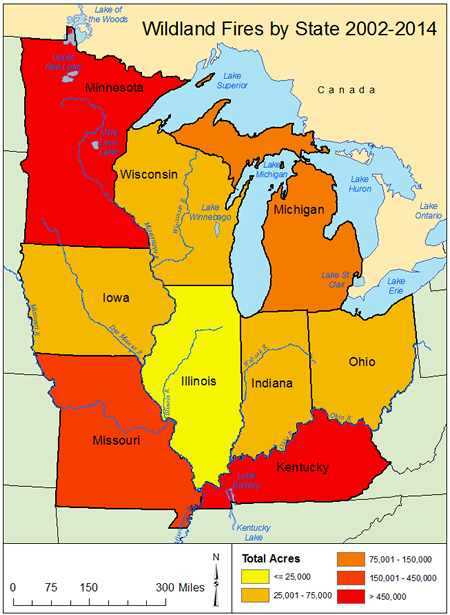

According to data provided by the National Interagency Fire Center for the years 2002–2014, an average number of 10,949 wildland fires occur in the Midwest, and an average of 214,843 acres are burned every year. Minnesota is the state most frequented by wildland fires in terms of total fires, average total fires per year, total acres burned, and average total acres burned. It is followed by Kentucky (2nd most active) and Wisconsin (3rd most active) for the total number of fires from during those years and the average total wildland fires per year. For total fires and average total fires per year, Illinois is the least active state for wildland fires annually. However, when reviewing the total acres burned per year, Indiana has experienced the least amount of burned acres for the time frame of 2002-2014. When reviewing the lowest average number of total acres burnt per year, Illinois is once again the leading state in least average number of total acres burned from wildland fires. The table below provides numbers for all states and are ranked highest to lowest for each category. The maps provide a visual of these statistics for the Midwest States.

|

State |

Total Fires |

State |

Average Total |

State |

Total Acres |

State |

Average Total Acres |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Minnesota |

23741 |

Minnesota |

1826 |

Minnesota |

799340 |

Minnesota |

61488 |

|

Kentucky |

19127 |

Kentucky |

1471 |

Iowa |

528119 |

Kentucky |

40625 |

|

Wisconsin |

16012 |

Wisconsin |

1232 |

Wisconsin |

304447 |

Wisconsin |

23419 |

|

Missouri |

14413 |

Missouri |

1109 |

Ohio |

97472 |

Missouri |

7498 |

|

Indiana |

8994 |

Indiana |

692 |

Kentucky |

59173 |

Indiana |

4552 |

|

Michigan |

6531 |

Michigan |

502 |

Missouri |

56367 |

Michigan |

4336 |

|

Ohio |

6144 |

Ohio |

473 |

Illinois |

38895 |

Ohio |

2992 |

|

Iowa |

2830 |

Iowa |

218 |

Michigan |

38320 |

Iowa |

2948 |

|

Illinois |

745 |

Illinois |

57 |

Indiana |

11452 |

Illinois |

881 |

LEFT: Midwest map of total wildland fires by state 2002-2014. Data Source: National Interagency Fire Center Maps created using ArcGIS. RIGHT: Map of Midwest wildland fires – total acres burned by state 2002-2014. Data Source: National Interagency Fire Center. Maps created using ArcGIS.

Map of fire regime areas in the United States from Brown, J.K. and J.K. Smith, 2000:

Wildland fire in ecosystems: effects of fire on flora. Gen. Tech. Rep.

RMRS-GTR-42-vol. 2 40,56-68. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station.

Retrieved on 2008-07-20

Historic Midwest Wildland Fires

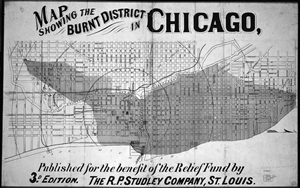

Great Chicago Fire, 1871

The Great Chicago Fire that burned from October 8-10, 1871 is one of the most commonly known historic fires in the

Midwest claiming the lives of up to 300 people. While not a true wildland fire, overly dry and windy climatic

conditions influenced the rate at which the fire spread through the city. Articles: History.com, and Great Chicago Fire.org.

Map of Chicago with burned region from the great Chicago fire in dark grey. Source: University of Chicago Press

Peshtigo Fire, 1871

The Peshtigo Fire on October 8, 1871 occurred on the same day as the Great Chicago Fire in Peshtigo, WI and the

surrounding areas. It is believed to have resulted from strong winds blowing embers and ashes from fires set

to clear forests and farmland. The fire quickly raged out of control from the winds and crossed over the Peshtigo

River. Over 1,000 people perished and over 1 million acres of forest burned. Articles: Peshtigo Fire.info.

Map showing the burnt area of the Peshtigo fire. Image courtesy of Exploring off the beaten path.com

Great Michigan Fire, 1871

The Great Michigan fire occurred at the same time as the Peshtigo and Chicago fires (October 8, 1871) and resulted

from logging debris catching fire after smaller land-clearing fires got out of control from the high winds. The

summer leading up to the fires had been very dry. The Port Huron Fire occurred on October 8, 1871, and is one of a

series of fires considered part of the Great Michigan Fire. It burned the cities of White Rock and Port Huron in

Michigan, killing at least 50 people. Additional fires were reported in the cities of Holland and Manistee,

Michigan. Over 1 million acres burned. After-effects of the Port Huron Fire helped fuel the “Thumb Fire”

of Michigan that occurred on September 5, 1871. The Thumb Fire burned over a million acres in one day and killed 282

people in Sanilac, Lapeer, Tuscola, and Huron counties. Articles: University of Michigan and Huron Daily Tribune, MI.

Map showing all the major fires October 8-21, 1871 across the Midwest. Source: Wunderground.com

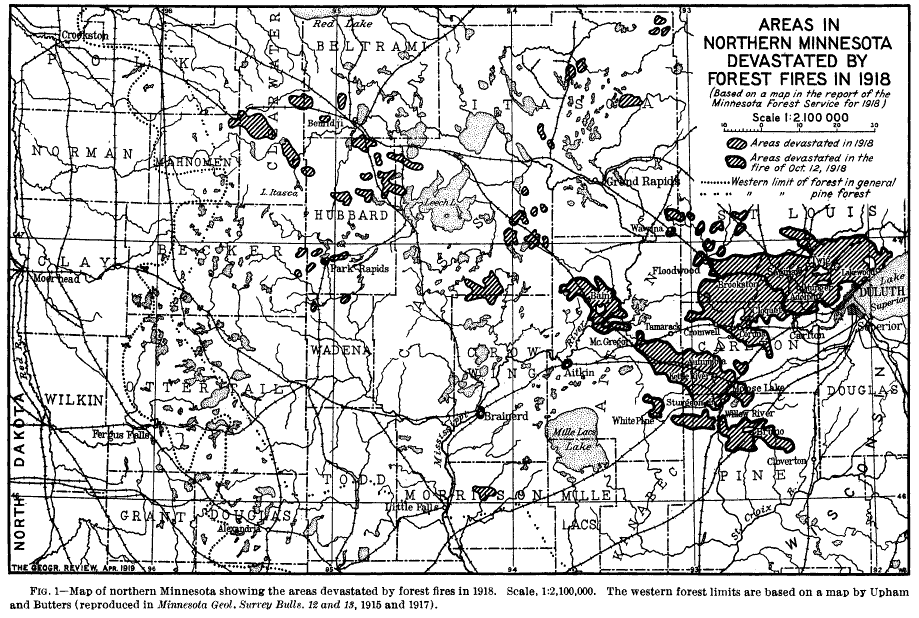

Cloquet Fire, 1918

The Cloquet Fire of October 1918 is one of Minnesota’s worst natural disasters. The fire ignited from a rail

car producing sparks along the rails that fell into dry brush along the railroad bed. Drought had been persistent

before the fire, thus 250,000 acres burned and 453 lives were lost. The primary impacts were felt in Moose Lake,

Cloquet, and Kettle River with Cloquet being the hardest area impacted by the fire. Articles: History.com and Content Time.com,

Map of the Cloquet Fire and additional fires that impacted Minnesota October 1918.

Source: www.jstore.org

The Role and Importance of Wildland Fires

Wildland fires play an important function in the natural ecosystems across Earth. There exist fire-dependent ecosystems, fire-sensitive ecosystems, and fire-independent ecosystems. Of all the ecoregions assessed around the world, half of Earth’s ecoregions (53%) are fire-dependent; 22% are fire-sensitive, and 15% are fire-independent. The remaining 10% of ecoregions have not been assessed.

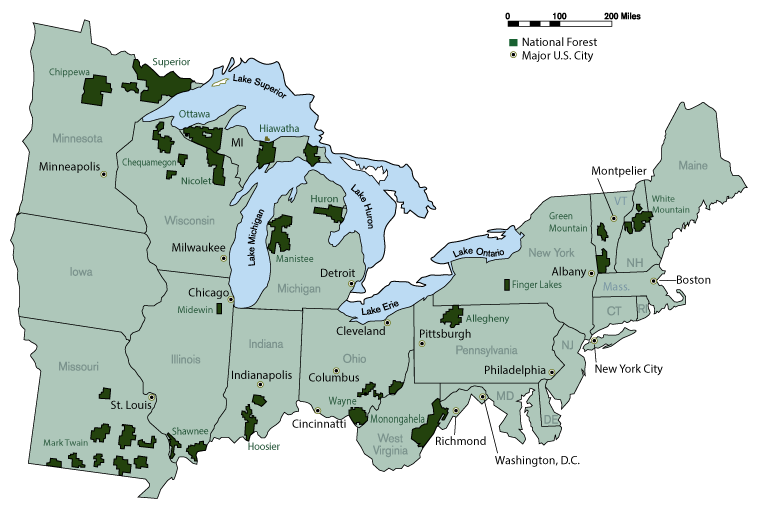

Map of the United States Forest Service Eastern Region, which includes the Midwest. Dark

colored areas are

national forests that are monitored for and maintained with wildland fires. Source: USDA -

Forest Service

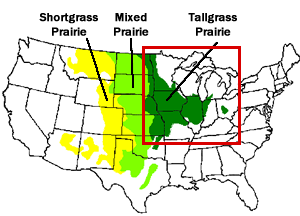

Map of Prairie Lands. The Midwest is boxed in red for clarity. The Midwest is predominantly covered by the Tallgrass Prairie fire-dependent ecosystem. Image courtesy USDA.

Fire-dependent ecosystems contain plant and animal species that have evolved to respond positively to fire. This means that these ecosystems require wildland fires to reproduce and grow and recover and grow in such a way as to help fires spread. The Midwest Tallgrass Prairie, the primary ecosystem covering the Midwest, is an example of a fire-dependent ecosystem. Forested regions of the Midwest, such as the North Woods in the upper Midwest and the Jack Pine forests in the Great Lakes region are also fire-dependent ecosystems. Understory wildland fires in these forests serve to remove excess dead leaves, twigs, branches, and grasses or shrubbery that inhibit new tree growth. Larger wildland fires in these forests serve to replace the larger trees that may be dying or have become too crowded for healthy growth.

The health of the Tallgrass Prairie ecosystem relies on wildland fires and grazing by animals for continued growth and health. Grazing animals stimulate plant growth, while fires burn off excess biomass that accumulates each year as grasslands and plants head into dormancy during winter. Burning of the excess biomass produces ash that provides nutrients to new growth that occurs during spring and summer.

Images of Jack Pine in Minnesota prone to forest fires, and burning prairie grasses.

Images courtesy UCAR.

Wildland Fire Types and Causes

Types of Fires

Fires are classified according to where and what they burn, along with how the fire starts. A wildland fire is any non-structure fire that occurs on land area where development is minimal except for roads, railroads, and utility lines. Three types of wildland fires have been further defined:

- Wildfire: an unplanned, unwanted wildland fire that includes unauthorized human-caused fires, escaped, prescribed fire projects, and all other wildland fires set with the objective to help extinguish another fire

- Prescribed fire: any fire started by fire management personnel through actions to meet specific objectives such as the establishment or maintenance of healthy forests and grasslands. Prescribed fires serve to reduce the buildup of hazardous fuels and are utilized more often near developed areas

- Wildland fire: a managed fire set in response to a naturally ignited wildland fire to accomplish specific resource management objectives in pre-defined areas as discussed in fire management plans

Natural Wildland Fire Environments

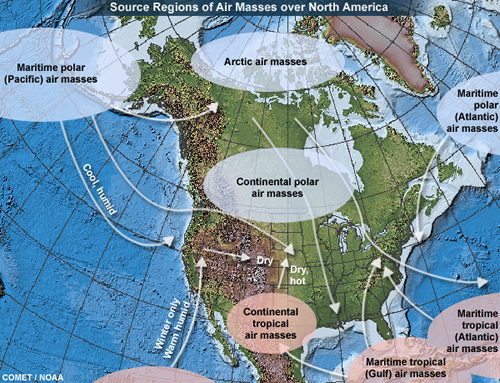

Wildfires most commonly occur in environments with warm, dry air and fuels containing minimal to no moisture. The atmosphere naturally generates large pockets of air called airmasses that are characterized by temperature and moisture. Airmassess that originate over land result in drier air, and airmasses that originate over oceans lead to moist air. The airmass predominantly affecting the Midwest that favors wildland fire development is the Hudson Bay High Pressure System. This high pressure system further dries and warms air through daytime heat from the sun and the Earth’s surface as it tracks from the north into the central region of the U.S., or from the northwest if it is impacting Ohio or New England.

Left: Map of airmass source regions in North America. Right: Map showing the location of

airmasses responsible for wildfire weather in the United States. Source: COMET Program of UCAR and NOAA

^Top

Ignition Sources

There are two types of ignition sources for wildland wildfires: natural sources and human-caused ignition.

- Natural forms of fire ignition primarily occur in the form of cloud-to-ground lightning from thunderstorms. The amount of rain produced by a storm can influence the potential for a lightning strike to ignite a fire, and for that fire to continue to spread. Lightning as an ignition source has been classified as dry, wet, or wet/dry lightning, which describes the amount of “wetting” rain or how much rain a thunderstorm produces. If enough rain is produced by the thunderstorm, the added moisture can decrease fire risk.

- Human-caused ignition results from humans being careless with fire ignition sources such as cigarette butts, not fully extinguishing campfires, the careless burning of trash or land debris, etc.

Fuels

Fuels are items that produce energy when burned. In the case of wildfires, this ranges from vegetation to human dwellings. In addition to taking into account the amount of fuel present, the condition of the fuel (how dry or wet) is highly important when determining the risk of wildfire. The season and growth stage of different types of vegetation can further change the fuel status or “dryness”. If climatological extreme events such as drought are occurring, these events must be considered as well. Fuels are further characterized by fuel type such as forests (soft or hard woods), canopy (closed or open), shrubbery (dense or sparse), or developed (urban, industrial, or residential).

Fire Spread

How a wildfire spreads is influenced by a number of highly complex interactions between various weather components such as precipitation (that fell either beforehand, during, or after the fire ignites), temperature, humidity, winds, and atmospheric stability. Fuel type, how much fuel is available (fuel loading), if the fuel is evenly spread out or bunched together in areas (fuel continuity), and topography characteristics (terrain configuration) further influence how wildfires spread. Fire behavior describes the processes by which fuels ignite, flames develop, and fire spreads.

Weather is the most variable of all factors that influence fire behavior. Wind, temperature, and humidity all contribute to fire evolution and spread. Winds push fires towards new fuel sources, pick up and transfer burning debris that can ignite new fires, and further dry out fuel sources. Temperature directly contributes to fire because it determines how quickly fuels will ignite because it speeds up the process of fuel reaching its ignition point. Fires in the shade do not burn as quickly as those in the path of direct sunlight. Humidity is a measure of the amount of moisture in the air. The moister the air, the damper the fuel and the less quickly fuel will burn. This slows the spread of flames. The drier the air, the more quickly fuel will burn, speeding up the spread of flames. Relative humidity is usually greater at night (and less during the day), so fires often burn less intensely at night.

Topography and how solar radiation heats hills, mountains, valleys, and slopes can also determine how fires spread. During the day, slopes heat up faster than other areas from solar radiation. Warmer air is lighter and rises, drawing air currents and fires up slopes. At night, air cools and sinks down slopes because it is heavier. This results in down-slope air currents and down-slope fire movement at night. The science behind wildfires is complex! It requires knowledge of chemistry, physics, geology, meteorology, and ecology.

Fire regime is a term used to describe the general pattern and conditions by which wildland fires naturally occur in an ecosystem over time. A fire regime is determined by characteristics such as fire frequency, intensity, severity, seasonality, size of burn, fire spread pattern, and pattern and distribution of burn. An altered fire regime is one that is typically modified by human activities to the extent that the current fire regime negatively impacts the ability of the ecosystem to prosper.

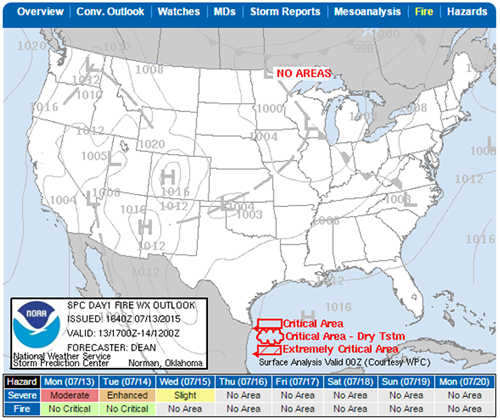

Know How to Get Local Fire Information

National Weather Service

Fire Weather Watches: Fire Weather Watches are issued when there is a high potential for the development of a Red Flag event (event in which wildland fires are probable in an environment given an ignition source). They are typically issued 18 to 96 hours before Red Flag criteria is expected to be met (NOAA NWS Directives 2013).

Red Flag Warnings: These are issued by your location's National Weather Service Forecast Office when conditions on fuel dryness and weather parameters combine to present conditions suitable for fire danger within 48 hours. Criteria may include but is not limited to: lightning episodes, significant dry frontal passage, strong winds, very low relative humidity, and/or dry thunderstorms. Additional parameters considered are drought status and fuel dryness in the region.

Storm Prediction Center (SPC) Fire Weather Outlooks: This is a product mainly used by NWS forecasters to help guide their decision making when issuing Fire Weather Watches or Red Flag Warnings. For the public who wish to remain situationally aware, the map highlights “areas of the continental U.S. where pre-existing fuel conditions, combined with forecast weather conditions during the next 8 days, will result in a significant threat for the ignition and/or spread of wildfires.”

Burn Notices, Burn Bans, and Burn Permits

These items are issued by different agencies and municipalities within each state to help control unintentional wildland fires. Counties or local authorities/governments (municipalities – villages, towns, or cities) may also regulate open burning in areas where they have been granted jurisdiction. It is important to note that local governments with no burn notices or bans still have to abide by any burn notices or bans set forth by the county or state. And if a state burn notice or ban is not in effect, but a local burn notice or ban is in effect, one has to abide the local burn notice or burn ban. It is suggested you consult county offices for resources on burn permits and information on any burn bans that may be in effect in the area.

Wildfire Mapping and Tracking Services

- NOAA Satellite and Information Service Hazard Mapping System Fire and Smoke Product

- USDA Forest Service Active Fire Mapping Program (updates on Fridays or as fire conditions warrant.)

- Esri Disaster Response Program US Wildfire Activity Map

Protect You and Your Home from Wildland Fires

Ready.gov suggests you be prepared for all natural disaster emergencies by making sure you have an emergency preparedness kit made up and easily accessible for you and your family, and a family communication plan in place to implement during an emergency situation. While this is more readily applicable to homes near forested areas, wildland fires on grass lands can occur so it is better to be over prepared than under prepared!

If a Fire Occurs:

- Listen to the local media for updates and be ready to leave at any time

- Account for all family members and know their locations

- Keep your indoor air clean – close windows and screen doors

- If you lack an air conditioner and it is too hot to remain inside because a fire is in close proximity, seek shelter elsewhere

After a Fire Occurs:

- Do not return to your home until fire officials give clearance

- Be cautious and avoid downed power lines, poles, or wires

- Check for smoke or burning embers throughout your home, as wildfire winds can blow burning embers from a

distance and reignite the fire

Wildland Fire Protection

The Basics:

- Keep fire and police emergency telephone numbers in easy-to-see and access locations

- Teach family members how to use an ABC fire extinguisher and keep several on hand around the house. Ideally one on each level of the home, one in the kitchen, and one in the garage

- Teach your children about fire safety and keep matches and lighters out of their reach

- In the case of a wildland fire, make sure you have planned several escape routes away from your home - by car and by foot

- Be aware of and follow your local burn laws

- Notify local authorities and obtain a burning permit before burning debris

- Keep a fire extinguisher or garden hose close by when burning items outdoors

- Report hazardous conditions that could cause a wildfire such as a neighbor carelessly burning trash or waste illegally

Landscape Maintenance:

- Create at least a 10-foot clearing with no vegetation or flammable materials around an incinerator, fire pit, propane tank, or grill before burning anything

- Regularly mow your lawn, rake up dead leaves, limbs, twigs, and vegetation and remove dead branches that extend over your roof

- Remove leaves and rubbish from under structures, and remove vines from your house walls

- Trim branches away from stovepipes and chimneys

- Regularly clean your roof and gutters

- Stack firewood at least 100 feet away from your home.

Property Maintenance:

- Inspect your chimneys twice a year, and clean them at least once a year. Keep dampers in working order and equip chimneys and stovepipes with spark arresters

- Place stove, fireplace, and grill ashes in a metal bucket and soak in water for 2 days. Afterwards, burry the cold ashes

- Store gasoline, oily rags and other flammable materials in approved safety cans. Place cans in a safe location away from the base of buildings

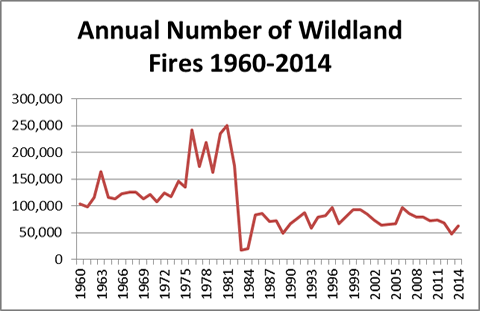

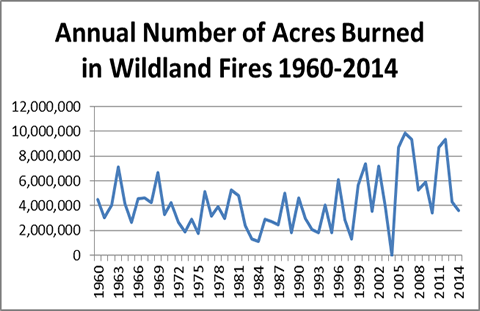

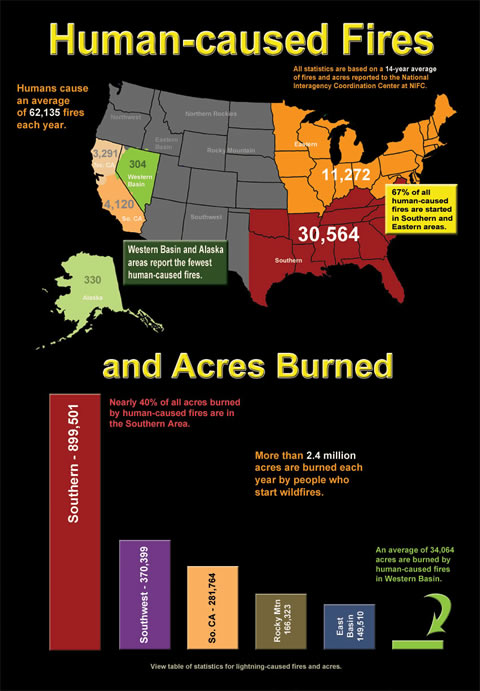

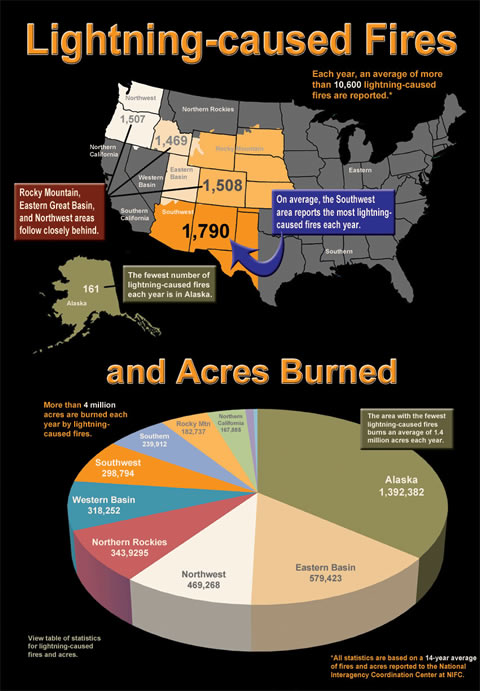

U.S. Wildland Fire by the Numbers

Data provided from nifc.gov. It is noted on the webpage that data prior to 1983 may be revised as NICC

verifies historical data.

Source: National Interagency Fire Center: Humans and National Interagency

Fire Center: Lightning

Wildfire Resources

References

Heartland News, 2015: Weekend rain helps extinguish most of Reynolds Co. wildfire. 11 May 2015. (Accessed 3 June 2015.)

National Interagency Fire Center. 2015. Communicator’s Guide: Wildland Fire. (Accessed 23 April 2105.)

Shlisky et al., 2007 “Fire, Ecosystems and People: Threats and Strategies for Global Biodiversity Conservation” (pdf)

Wachter, et al., 2008: Fire Weather Climatology Lesson, Unit 3 of the Advanced Fire Weather Forecasters Course. The COMET Program. University Corporation of Atmospheric Research. 28 March 2008.