Lightning

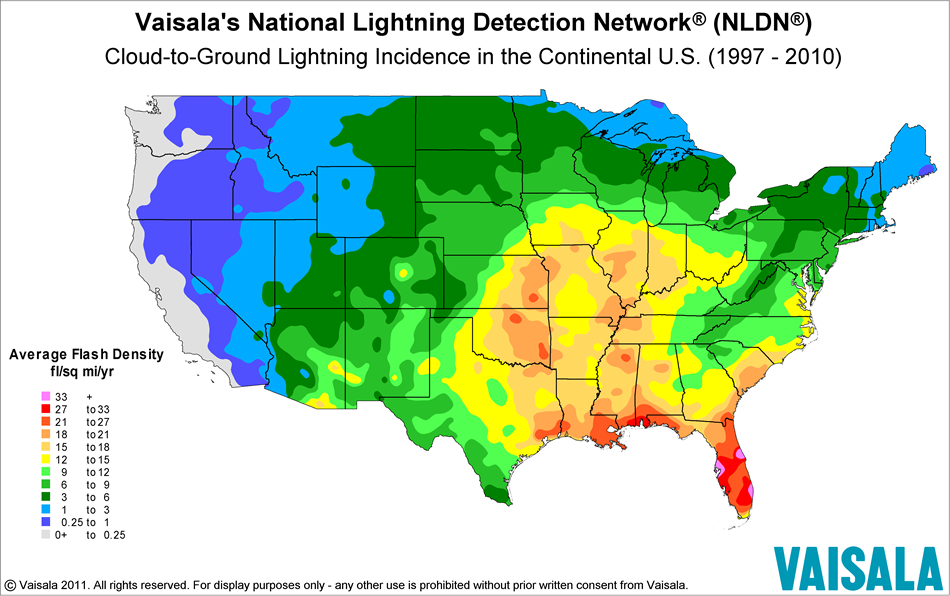

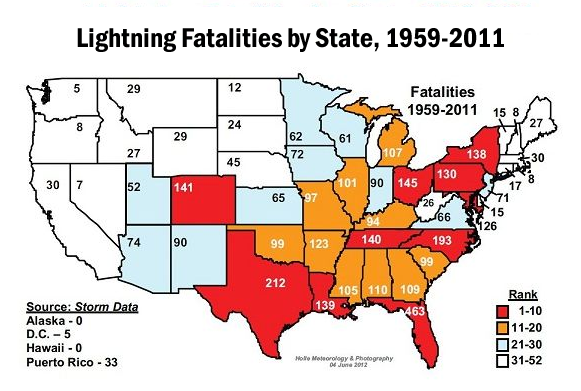

Lightning is one of the oldest observed natural phenomena on earth. It occurs throughout the country, but especially in the Southeast, Midwest, and front ranges of the Rocky Mountains. Hundreds of people are struck by lightning each year, resulting in an annual average of 50 deaths in the U.S. While some 90 percent of people survive lightning strikes, survivors often suffer devastating life-long injuries. Knowing about lightning and lightning safety may protect you from one of the most erratic and unpredictable characteristics of a thunderstorm.

What is Lightning?

Lightning is a sudden electrostatic discharge from a thunderstorm, the most common but least understood of weather

phenomena. These giant sparks can extend from the cloud to the ground or objects on the ground, between clouds,

within the cloud, or even between the cloud and air.

Lightning is a sudden electrostatic discharge from a thunderstorm, the most common but least understood of weather

phenomena. These giant sparks can extend from the cloud to the ground or objects on the ground, between clouds,

within the cloud, or even between the cloud and air.

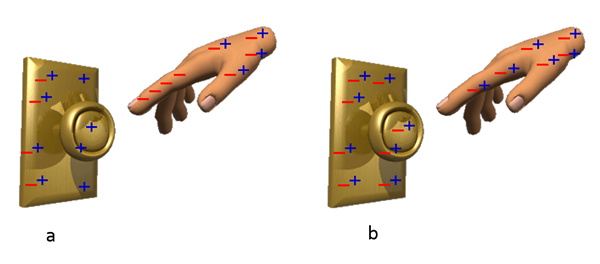

In many respects lightning is similar to the static electricity spark you may see or feel during the winter when the air is very dry and you touch a metallic object. When you walk across a carpet, for example, electrons move from the atoms in the carpet to you. You are, in effect, negatively charged. When you touch a metallic object like a door knob, the electrons move from you to the knob. The zap you feel and may hear are the electrons moving from you to the door knob through an electric spark.

a) When you walk across the carpet, electrons move from the carpet to your body, giving you a negative charge.

b) When you touch the door knob, the excess electrons move from you to the positively charged door knob. You and the door knob now have a neutral charge.

Graphic designed by Steve Hilberg, Midwestern Regional Climate Center.

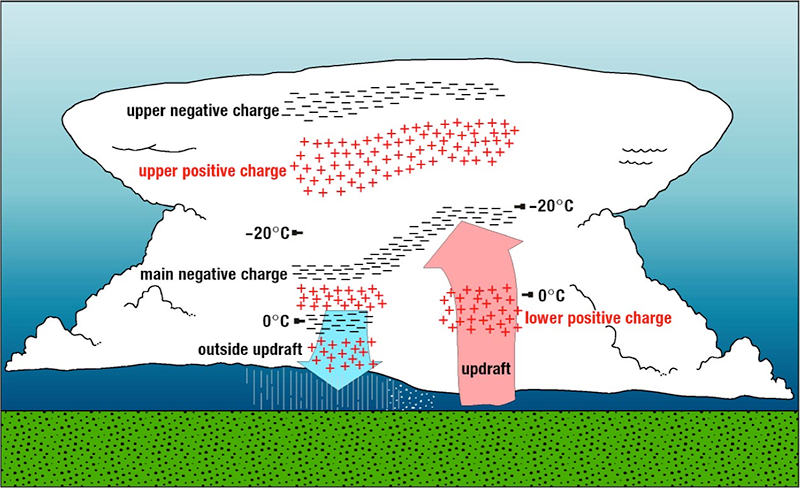

Similar processes occur in a developing thunderstorm. As the thunderstorm develops the updrafts and downdrafts within the storm result in collisions between the precipitation particles within the cloud. Near the top of the storm these are usually small ice crystals. The ice crystals become positively charged and are carried higher into the storm because they are lighter. As a result the top of the storm becomes positively charged, while the middle and lower layers become negatively charged. Small ice crystals and small hail occur in the middle of the storm, while in the lower layer raindrops and melting hail occur. The collisions between these particles cause some to lose electrons and become negatively charged. The negative charge in the middle and lower layers of the thunderstorm cloud induces a positive charge in the ground underneath the storm, and the positively charged anvil induces the ground under the anvil to become negatively charged.

What happens when lightning occurs?

In the early stages of thunderstorm development the air acts as an insulating layer between the cloud and its surroundings. As the electrical charges build up within the thunderstorm, the difference between, for example, the negatively charged middle portion of the cloud and the ground become large enough to overcome the insulating effects of the air, and a lightning discharge occurs. When this discharge occurs between the middle of the cloud and upper portion of the storm, “in-cloud” lightning occurs. When the discharge occurs between the negatively charged region of one storm and the positively charged region of another, it is called cloud-to-cloud lightning. Cloud-to-ground lightning occurs when the discharge happens between the cloud and the ground.

Schematic of how electrical charges are typically distributed in a

thunderstorm. Credit: National Severe Storms Laboratory

Cloud-to-ground lightning strikes account for about 25 percent of the lightning flashes worldwide. They are some of the most spectacular and also the most dangerous because they hit the ground or objects on the ground. The lightning discharge lasts only a few microseconds, but the process of its formation is complex.

A lightning strike begins when an ionized channel of air, called a step leader, develops from the thunderstorm to the ground. As the step leader zigzags toward the ground, the electrical field increases as the quantity of positive charge residing on the Earth's surface becomes even greater. The electric field is strongest on grounded objects whose tops are closest to the base of the storm such as trees and tall buildings (that’s why you stay away from tall objects during a thunderstorm). This charge begins to migrate upward through buildings, trees and people into the air. When this upward rising positive charge – an upward leader or streamer – meets with the leader in the air above the surface, a conductive path is completed. Electrons surge along this path creating the visible lightning bolt. The rapid flow of electrons heats the surrounding air causing it to explosively expand, sending out a shockwave we hear as thunder.

The Dangers of Lightning

Lightning is the third highest cause of weather-related deaths after flooding and extreme heat causing an average of 51 fatalities a year, with many more injured. Lightning can occur at any time of the year in the U.S. but mostly occurs in the spring and summer months. This coincides with the times that people are most likely to be engaged in outdoor activities, increasing their risk of exposure to lightning. The highest frequency of lightning strikes in the U.S. occurs in Florida and along the Gulf Coast.

According to the National Lightning Safety Institute, costs and losses due to lightning in the U.S. could be as high as $8 - $10 billion per year. Among the costs associated with lightning are lightning-caused wildfires, damages to homes and other structures, repair of damaged public electrical and communication utilities, and damages to electrical equipment, both residential and commercial.

Lightning also is a threat to personal safety especially if you are caught outdoors during a thunderstorm. However,

even people indoors have been injured or killed by lightning. There are five ways a person can be struck by

lightning.

A direct strike occurs when the person, usually in an open area, becomes part of the main lightning discharge channel. A portion of the current moves along and over the skin, and a portion moves through the body

A side flash occurs when the lightning strikes a taller object near the

person (like a tree) and part of the current jumps from that object to the person.

A person may also be affected by a ground current. When lightning strikes a tall tree, for example, the charge travels down the object to the ground and then along the ground surface. Ground current can cover a large area and is the cause of most lightning casualties. The current enters the body at the point closest to the lightning strike (for example, your foot) and exits the body at a point farthest away from the strike. The greater the difference between these two points the greater potential for injury or death. Ground current is often fatal to livestock because of their large size.

Turf damage caused by ground current from a lightning strike. Photo credit: AlGamaty on Reddit

Conduction of lightning through wires or other metal surfaces allows lightning to travel long distances. Fences, electrical lines, pipes, or other metal surfaces can provide a pathway for lightning. Most indoor lightning casualties are related to conduction. That is why it is important to stay off of a corded phone, and stay away from anything plugged into an electrical outlet, water faucets and showers, or windows and doors.

Streamers develop as the downward-moving leader approaches the ground. These are upward streamers, and usually only one of the upward streamers makes contact with the leader to provide the main channel for the return stroke. However, when the main channel discharges, so do all the other streamers in the area. If a person is part of one of these streamers, they could be killed or injured during the streamer discharge even though they are not part of the main discharge.

You can read more at the National Weather Service web site Lightning Science: Five Ways Lightning Strikes People.

What happens when you are struck by lightning?

When lightning strikes your home it may damage your computer, television, and other electronics. When lightning strikes a person the primary injuries are to the body’s “electronics” – the nervous system and the brain. The most readily apparent affect may be cardiac arrest. Serious burns seldom occur. Most burns are caused by other objects (rainwater, sweat, metal coins and necklaces, etc.) being heated by the current passing through them and causing the burn rather than being caused by the lightning itself. It’s estimated that only ten percent of people struck by lightning are killed. The remaining 90 percent of victims exhibit various degrees of short and long-term disability.

Damage to the nervous system and the brain may not be readily apparent. Symptoms may include fatigue, intense

headaches, inability to concentrate, inability to process information, personality changes, and others. Some

symptoms may not manifest themselves until sometime after the incident. Often conventional medical testing (imaging,

lab tests, etc.) will not show any physical changes that can be attributed to the lightning strike. Neurocognitive

or neuropsychological testing may be used to identify functional and cognitive deficiencies.

There is research being done on the injuries resulting from lightning. Dr. Mary Ann Cooper, M.D. at the University of

Illinois at Chicago heads the Lightning

Injury Research Program. Her article “Disability, not Death, is the Main Problem with Lightning Injury” contains more

information on the effects of lightning injuries.

The behavioral and personality changes that may be experienced by lightning-strike survivors are often hard for family and friends to understand. Lightning Strike & Electrical Shock Survivors International, Inc. is a non-profit support group formed by a lightning strike survivor in 1989. Its mission is to provide support for survivors, spouses, and other interested parties as well as to provide education on the prevention of lightning and electrical injuries.

Lightning Safety

Outdoors is the worst place to be in a thunderstorm – no place is safe. Fishing, boating, and camping top the

activities associated with the most fatalities from lightning. Soccer leads the list in sporting-related fatalities

followed by golf and running. Seventy percent of all lightning fatalities occur in June, July, and August. This is

not surprising considering that this is a time when people spend much more time outdoors and is also the peak of the

thunderstorm season.

What do you need to do to be safe from lightning?

“When thunder roars, go indoors!”

If you are outdoors, find shelter in a nearby safe building or metal-topped vehicle with the windows closed. If you can hear thunder then you are at risk from lightning. The furthest distance from a lightning strike you can typically hear thunder is about five miles and seldom more than 10 miles. Just because you can’t hear thunder doesn’t necessarily mean you are safe. Lightning bolts are known to arc out tens of miles from the parent thunderstorm. Stay inside at least 30 minutes after you last hear thunder.

Lightning arcing and striking some distance away from a thunderstorm located over the

Shenandoah Valley of Virginia.

Photo

Credit: Edward Payne Photography. Used with permission.

If you cannot find safe shelter there are some steps you can take to lessen your risk. However, it bears repeating that no place is safe outdoors in a thunderstorm.

- Avoid open fields, the top of a hill or a ridge top.

- Stay away from tall, isolated trees or other tall objects. If you are in a forest, stay near a lower stand of trees.

- If you are in a group, spread out to avoid the current traveling between group members.

- If you are camping in an open area, set up camp in a valley, ravine or other low area. However, be aware of flash flooding potential in low-lying areas. Remember, a tent offers NO protection from lightning.

- Stay away from water and wet items such as ropes, as well as metal objects such as fences and poles. Water and metal do not attract lightning but they are excellent conductors of electricity. The current from a lightning flash easily travels long distances.

If you are indoors,

- Stay off corded phones. You can use cellular or cordless phones.

- Don't touch electrical equipment such as computers, TVs, or cords. You can use remote controls safety.

- Avoid plumbing. Do not wash your hands, take a shower or wash dishes.

- Stay away from windows and doors that might have small leaks around the sides to let in lightning, and stay off porches.

- Do not lie on concrete floors or lean against concrete walls.

- Protect your pets: Dog houses are not safe shelters. Dogs that are chained to trees or on metal runners are particularly vulnerable to lightning strikes.

- Protect your property: Lightning generates electric surges that can damage electronic equipment some distance from the actual strike. Typical surge protectors will not protect equipment from a lightning strike. The National Lightning Safety Institute has information on protecting your home and electronics from lightning. Do not unplug equipment during a thunderstorm as there is a risk you could be struck.

The National Weather Service has much more lightning safety information on their Lightning Safety web page.

Myths about lightning

| Myth: | Lightning never strikes the same place twice. |

| Fact: | Lightning often strikes the same place repeatedly, especially if it’s a tall, pointed, isolated

object. The Empire State Building is hit nearly 100 times a year. |

| Myth: | Rubber tires on a car protect you from lightning by insulating you from the ground. |

| Fact: | Most cars are safe from lightning, but it is the metal roof and metal sides that protect you, NOT the rubber

tires. Remember, convertibles, motorcycles, bicycles, open-shelled outdoor recreational vehicles and cars

with fiberglass shells offer no protection from lightning. When lightning strikes a vehicle, it goes through

the metal frame into the ground. Don't lean on doors during a thunderstorm. |

| Myth: | Structures with metal, or metal on the body (jewelry, cell phones, MP3 players, watches, etc), attract lightning. |

| Fact: | Height, a pointed shape, and isolation are the dominant factors controlling where a lightning bolt will

strike. The presence of metal makes absolutely no difference on where lightning strikes. Mountains are made

of stone but get struck by lightning many times a year. When lightning threatens, take proper protective

action immediately by seeking a safe shelter - don’t waste time removing metal. While metal does not

attract lightning, it does conduct electricity so stay away from metal fences, railing, bleachers,

etc. |

| Myth: | If trapped outside and lightning is about to strike, you should lie flat on the ground. |

| Fact: | Lying flat increases your chance of being affected by potentially deadly ground current.

If you are caught outside in a thunderstorm, keep moving toward a safe shelter. |

| Myth: | If you're caught outside during a thunderstorm, you should crouch down to reduce your risk of being struck. |

| Fact: | Crouching doesn't make you any safer outdoors. Run to a substantial building or hard topped vehicle. If you

are too far to run to one of these options, you have no good alternative. You are NOT safe anywhere

outdoors. |

| Myth: | “Heat lightning” is caused by heat, not thunderstorms. |

| Fact: | There is no such phenomenon as heat lightning. “Heat lightning” is the name that at one time was given to ordinary lightning too far away for thunder to be heard. This term likely originated when people noticed distant lightning, usually at night, on warm summer evenings when skies above were clear. In some cases lightning may be visible a hundred or more miles distant. |

Lightning Data

The National Lightning Detection Network

The National Lightning Detection Network (NLDN) began operation as a regional network run by the State University of New York at Albany in 1983. The NLDN was eventually acquired by Global Atmospherics, Inc., and then in 2002 by Vaisala, Inc., a company that develops, manufactures and markets products and services for environmental and industrial measurement, especially meteorology and hydrology. The NLDN became national in coverage in 1989. It consists of over 100 remote, ground-based sensing stations located across the United States that instantaneously detect the electromagnetic signals given off when lightning strikes the earth's surface. These remote sensors send the raw data via a satellite-based communications network to the Network Control Center (NCC) in Tucson, Arizona. Within seconds of a lightning strike, the NCC's central analyzers process information on the location, time, polarity of the strike, and communicate this information to users across the country.

This lightning data is used by the utility industry, NASA, the National Weather Service, aviation, forestry, and many others. More information on the NLDN can be found here.

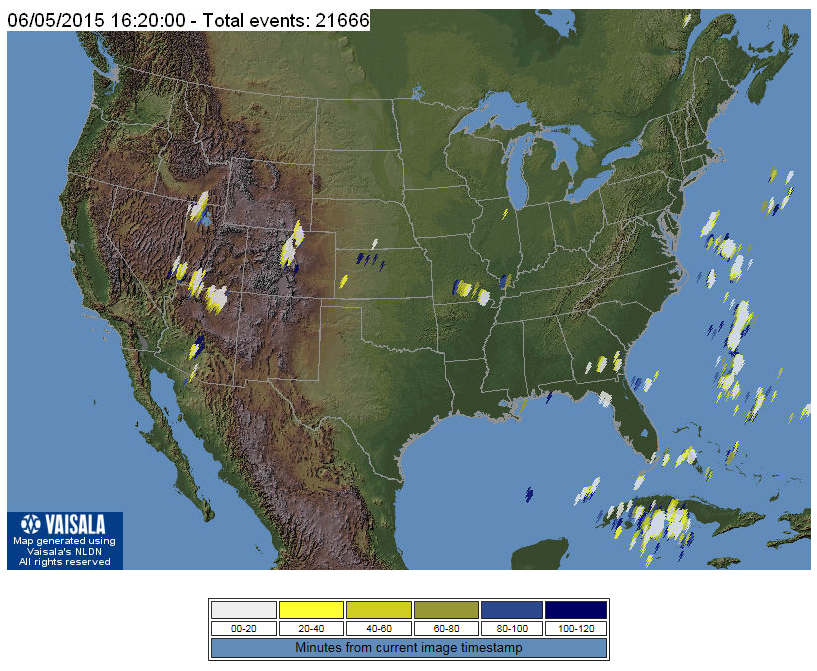

A map from Vaisala's "Lightning Explorer." Data on the map is 20 minutes

delayed and updated every 20 minutes.

Blitzortung

Blitzortung.org is a world-wide lightning detection network for the location of

electromagnetic discharges in the atmosphere (lightning discharges) based on the time of arrival (TOA) and time of

group arrival (TOGA) method. It was developed by a few people in Germany several years ago, and since has expanded

world-wide. This lightning detection network consists of volunteers with lightning detectors constructed from a kit

developed by the Blitzortung group. The detectors transmit data to a central processing server over the Internet,

which then processes the data to determine the location of lightning strikes. Other volunteers include programmers

who develop and/or implement algorithms for the location or visualization of sferic positions (sferics are a type of

radio signal produced by lightning), and people who assist to keep the system running. There are about 110 detection

stations in the U.S.

The web site includes a word-wide live map of current lightning strikes, an archive of lightning data, and information on how to obtain a kit to build your own lightning detector. The construction of the detector requires some knowledge of and skills in electronics.

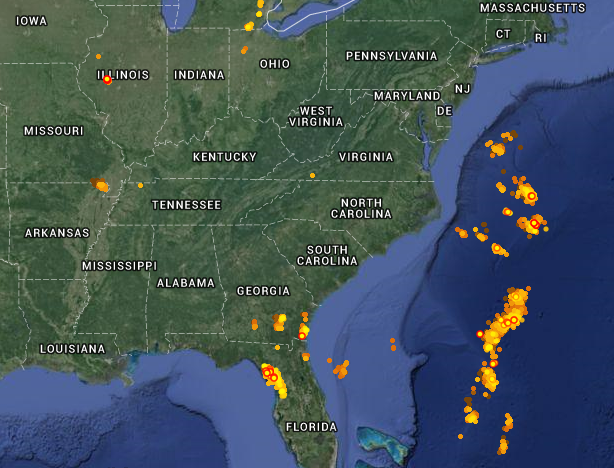

LightningMaps.org

LightningMaps.org is a community project with free lightning maps and applications. Real-time lightning data is available on a map-based interface utilizing the data from Blitzortung (below, left).

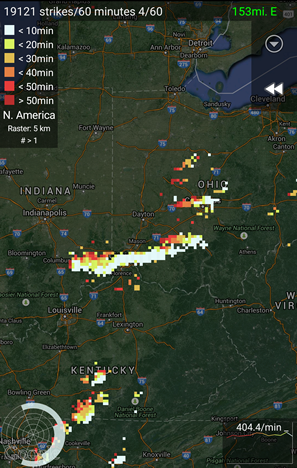

There are a number of apps available for your smart phone and tablet to display lightning strikes. A free Android app that uses the Blitzortung data feed is called "Blitzortung Lightning Monitor". It has a number of features, including alarms to notify you of nearby lightning strikes (above, right).

Lightning Resources

- Lightning in Super Slow Motion – video clip from Discovery Channel's "Raging Planet" on the subject of lightning.

- Lightning: JetStream – Online School for Weather

- Lightning Safety (NWS)

- Severe Weather 101: Lightning Basics

- National Lightning Safety Institute

- Medical Aspects of Lightning

- Human Voltage - What happens when people and lightning converge

- Lightning Strike & Electric Shock Survivors International, Inc.

- Lightning Injuries

- A Detailed Analysis of Lightning Deaths in the United States for the last ten years

- Lightning Climatology References

- Ready.gov Kids Pages -Ready Kids! - Emergencies can be scary, but the more you know about them, the better you can deal with what comes your way! This Ready.gov section also has games plus info geared toward parents and educators.