The Great Flood of 1913

100 Years Later

Community Profiles: Wabash, Indiana

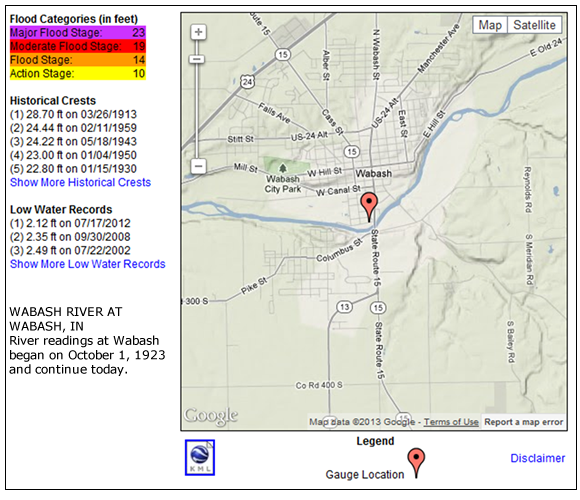

| River: | Wabash |

| Storm Total Rainfall: | At least 5" locally |

| Known Fatalities: |

Timeline

This article appeared in the Wabash Plain Dealer, Saturday, March 26, 1977.

When the Waters Came to Wabash

By Earleen Ulery, Community Affairs Editor

If spring ever roared in like the proverbial lion in Wabash County, it was Thursday, March 20, 1913.

What was to eventually lead to Wabash County’s record flood started about 10 p.m.

Thunderbolts were deafening, lightning flashes blinding, and rain poured down in torrents. Some people feared Wabash was having an earthquake that would rival San Francisco’s famous disaster.

By 3 a.m., March 21, the rain was subsiding and a strong wind arose playing tiddly winks with barns, outhouses, sheds, roofs, telegraph, telegram and trolley lines. Signs and billboards, chimneys and smokestacks suddenly left their resting places.

Beitman and Wolf lost its plate glass window, Yarnelle Lumber Mill shed blew over onto Canal Street, and Riley Johnson’s large wooden sign at the west door of the Plain Dealer building was blown into the street and broken. Silos went down. School hack drivers had to do acrobatics with rain-drenched roads to deliver their charges to county schools.

The rains began again on Sunday, March 23rd; saturated Wabash County lands refused to absorb the droplets and they streaked toward every river and stream they could find. Finally something had to give, for the Wabash River banks could hold no more.

But there seemed to be no rush about getting ready for the impending flood. The river continued to rise on Sunday and by evening it was full, bank to bank, yet there appeared no uneasiness among the lowlands people. By Monday, March 24, people were saying the flood would surpass the ice gorge-caused flood of 1883 that had made all-time history. One writer said the unprecedented eight-hour rise had taken the people unawares and their homes were surrounded before they realized the danger.

By 1 a.m., homes were flooded and rescue operations underway. The interurban tracks were under 10 feet of water and had not been in sight for 12 hours. Household goods were stacked in second stories, and women and children taken from their homes by skiffs. By 7 a.m., flood waters had reached Yarnelle Lumber Mill. Factories in the lowlands were closing down. Hundreds of logs floated downriver. The river continued rising four to five inches an hour.

That Monday night became known for its terror. The next morning, Memorial Hall and the Christian and St. Bernard churches were pressed into service. The flood reached a height Wabash people had never known, and it would be another day before it would crest at 28.7 feet—the highest ever recorded.

Impacts

If Wabash had ever been in chaos, it was that night.

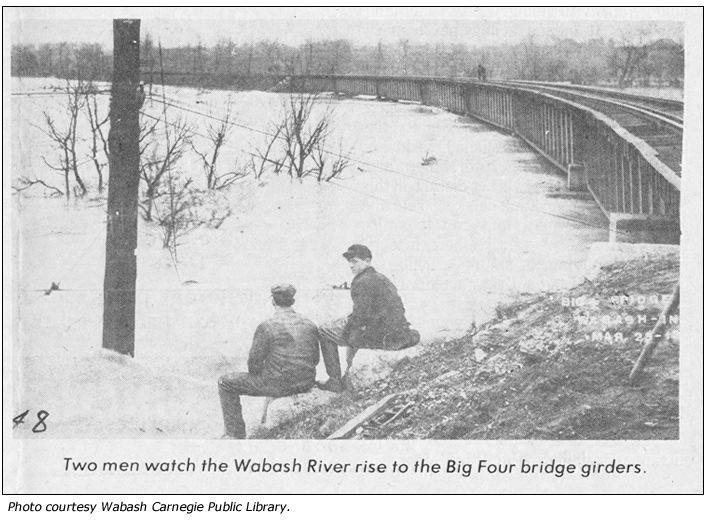

The city was without lights, commercial power and telephone service. Traffic was suspended on railroads and interurbans. Water rushed up against the large steel girders of the Big Four Railroad Bridge and many feared the bridge would be washed downstream. In an effort to save the bridge, 15 carloads of coal and a large carload of logs were placed on the

bridge. Wires were stretched on the East side to prevent the drift from striking the bridge.

bridge. Wires were stretched on the East side to prevent the drift from striking the bridge.

By Wednesday, the water supply in the stand pipe was exhausted, leaving the city without fire protection and residents without water for domestic purposes. Wabash Water and Light Company powerhouse was under water and it would take another 10 days for repairs.

The rush was on at grocery stores for coal oil and lamps. Standard Oil supplies were under 15 feet of water. Eventually Mayor James Wilson had to ration coal oil, one gallon per person.

Wabash High School (now the city schools’ administration building) was closed because water backed up in the sewer into the boiler room, shutting down the heating system.

A tally showed 720 Wabash inhabitants were homeless and many were at the mercy of charity.

Because there was little fire protection Mayor Wilson ordered all businesses closed at 6 p.m. and no one was to be on the water in boats after that hour. City Council appropriated $1,000 for flood victims and County Council was pressed for additional funds.

During the worst of the flood, meals were cooked at Memorial Hall and served by churches. Women and girls were housed at the Christian Church and men at St. Bernard Church. The county courthouse also was used.

Old timers recalled the river was 20 inches higher than it had ever been before, even in 1847 when canal boats traveled along Canal Street to rescue citizens.

Within a few days the Red Cross sent in mattresses, comforters and blankets, and citizens donated funds for their less fortunate townspeople.

Wabash residents were warned to boil all water as the enormous rainfall had acted as a solvent for accumulated filth everywhere. Germs were bound to be present.

[The towns of] Lagro and Richvalley had corresponding problems, and cold complicated matters. Peru was far worse off than Wabash. Lives were lost and part of the circus washed away. The Wabash Railroad work train made an unsuccessful attempt to take several hundred loaves of bread, blankets, and clothing to the circus city. Wabash seemed to be almost isolated—even the wagon roads were blocked by fallen trees.

People still were being fed at Memorial Hall on April 4, but people were moving back into their homes. The health department put barrels of lime at every alley and street corner in the flooded district so people whose homes were submerged and flooded would have easy access for use in cellars, outhouses, barns, and chicken coops.

Flood loss at the Manson Story garage totaled $500 when cars belonging to Mrs. Harry King and Homer Goodlander couldn’t be removed. Damage at Wabash Baking Powder Co., was to tin plate and stacked paper, which were submerged. At Yarnelle Lumber, the office was completely submerged with water up to the eves in the factory, and lumber floated away.

Hay, corn, and oats were soaked at the E.E. Smith feed exchange on South Miami Street and at Talbert Barns, West Canal Street, where it was feared some horses would be lost by sickness. Flashes and patterns belonging to Wabash Foundry and Machine Company, south Carroll Street, floated away. Heaviest industrial loses were at Wabash Coating Mill, $10,000; Wabash Cabinet Co., $15,000, and at United Boxboard and Paper Mills, $25,000.

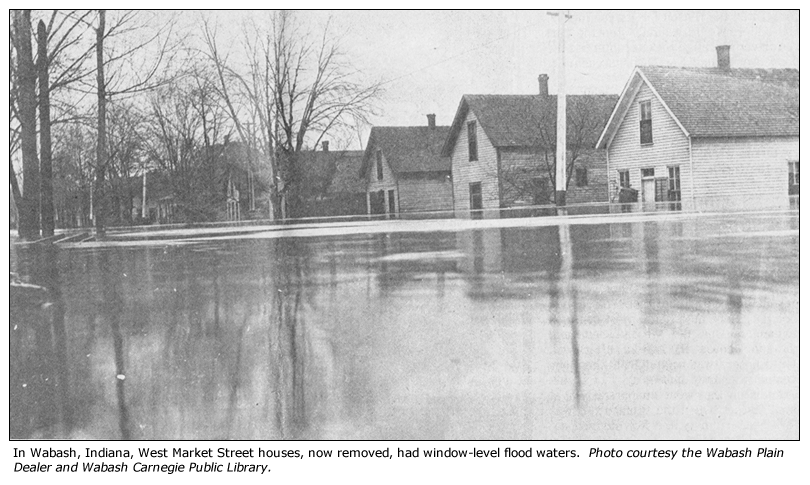

Through it all, thousands of persons read the bulletins posted in the Plain Dealer windows on West Market Street.

By April 1 factories started reopening. But residents were still having a hard time drying out homes. Every bridge in Wabash County had some damage and estimated costs ran between $40,000 and $50,000 for repairs. There was great damage to the roads. City Council considered building a levee, but prospects were that the matter would wait to be taken up with federal authorities.

And damaging floods came again and again. Between 1913 and 1973, the Wabash River reached a stage where moderate damage was caused at least 14 times. Warning stage is 17 feet. Between 1913 and 1959, the river crested at over 20 feet 13 times, reaching as high as 24.44 feet in 1959.

Thanks to Tracy Stewart, Executive Director of the Wabash County Historical Museum, for providing this article.

Flood Protection Measures

Three Corps of Engineers reservoirs (JE Roush and Salamonie ) provide combined flood control benefits for 72% of the drainage area upstream of Wabash, and greatly reduce Wabash River flooding there.

To update information about the March 1913 flood story of Wabash contact Al Shipe by e-mail al.shipe@noaa.gov.