The Great Flood of 1913

100 Years Later

Community Profiles: Vincennes, Indiana

| River: | Wabash |

| Storm Total Rainfall: | 9.40" |

| Known Fatalities: |

Timeline

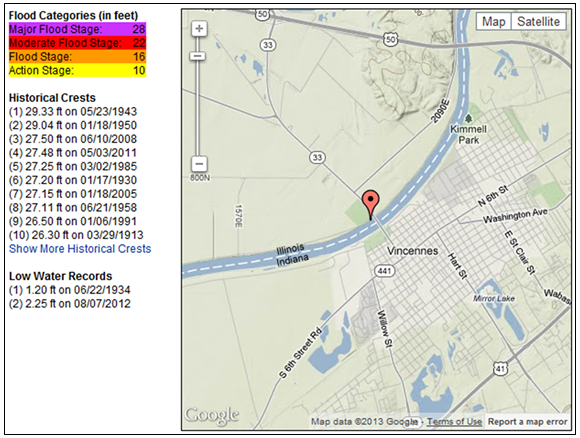

The March 1913 flood is the largest known volume flow for the Wabash River at Vincennes. Because local levees constrict the Wabash River at Vincennes, the March 1913 flood is no longer the highest by river gauge readings. The current gauge record of 29.33 feet was set on May 23, 1943 prior to a levee failure on the Illinois side of the river during the May 1943 flood, compared to a 26.30 foot crest (today’s datum) in March 1913.

The Wabash River broke all levees in the Vincennes area during March 1913 and was 7 miles wide. In May 1943, levees on the Indiana side held, but failed on the Illinois side. Low areas of Lawrence County flooded extensively...even greater than in June 2008. Comparing the estimated peak flood discharge of March 1913 (255,000 cubic feet per second) to the May 1943 (189,000 cubic feet per second), the May 1943 flood had about an estimated 75% of the flow of the March 1913 flood.

The following article in three parts was written by Brian Spangle, Historical Collection Administrator at McGrady-Brockman House, Knox County Public Library in Vincennes, Indiana.

1913 Flood of 100 Years Ago One of the Worst on Record - Part 1

This month marks the 100th anniversary of the March 1913 flood that caused death and destruction throughout much of the Ohio Valley. Heavy rains that fell on already saturated ground from March 23-27 caused flooding in virtually every community situated on a major waterway or its tributary.

Tornadoes accompanied the initial storms. On Easter Sunday, March 23, 21 people in Terre Haute were killed by a tornado. Ninety-four people died that day when a tornado hit Omaha, Nebraska. Indiana and Ohio were two of the worst states affected by flooding. Ohio’s Miami River Basin saw some of most dramatic devastation. A large section of Dayton was flooded and around 100 or more people in that city died. Parts of Dayton were destroyed by fire from a gas explosion.

In Indiana alone, flood damage would total in the tens of millions of dollars (and that was in 1913 dollars). Indianapolis, Peru, Terre Haute, and Muncie were among the many Indiana cities that had major flooding. At Peru, nearly a dozen people died. Peru was also the winter home of the Hagenbeck-Wallace Circus, and many circus animals, including a number of elephants, drowned.

The city of Vincennes and vicinity fared better than many Midwest towns, although the area still experienced its share of damage and suffering, as the Wabash River here reached a record-breaking crest. At Vincennes, the worst of the rain came on March 24 and 25, when, in a single 24-hour period, just over 6 inches of rain fell on the city. Heavy rains had also fallen on preceding days. Total March rainfall at Vincennes would be over 12 inches.

The rainfall sent Kelso Creek on a rampage and set the Wabash on a rapid rise. The creek was quickly out of its banks and parts of the city’s north and east sections were soon underwater. The worst backwater flooding came in what was known as the “Oklahoma” district in the north end. Parts of Chicago, Minneapolis, and Eberwine Avenues and areas over to Kessinger, Manilla, and Roussillon Streets were under as much as 3 feet of water. Many people had to be rescued from their flooded homes.

Backwater covered Fairgrounds Avenue (now Washington Avenue), as far as St. Clair Street and beyond. The Fairgrounds (now Gregg Park) and ballpark were flooded. Debris was floating everywhere. A hen setting on eggs was seen floating on debris near the county orphanage at Fairground Avenue and St. Clair Streets. Many other streets in the city were covered by water.

The railroads experienced much damage, hindering transportation. There were so many railroad washouts that trains either ran hours late or couldn’t get through at all. The miner’s train that traveled from Vincennes to the Indian Creek Mine southwest of Bicknell didn’t run, thus giving 200 coal miners a holiday. Gravel roads were also washed out.

On the afternoon of the 25th, the Wabash was at just over 16 feet and rising. More rain fell that day.

The city was bracing for what most anticipated could be the worst flood in its history. The previous high mark, at least since records were kept, had come on March 29, 1898 when, as reported in newspaper accounts of the time, the Wabash reached 23.1 feet. Long-time Knox County residents also had bitter memories of a severe flood in the summer of 1875. That year the Wabash crested at 21.7 feet on August 10, destroying wheat, corn, hay, and oat crops and drowning livestock. People could recall seeing wheat shocks, straw stacks, and dead livestock floating down the river.

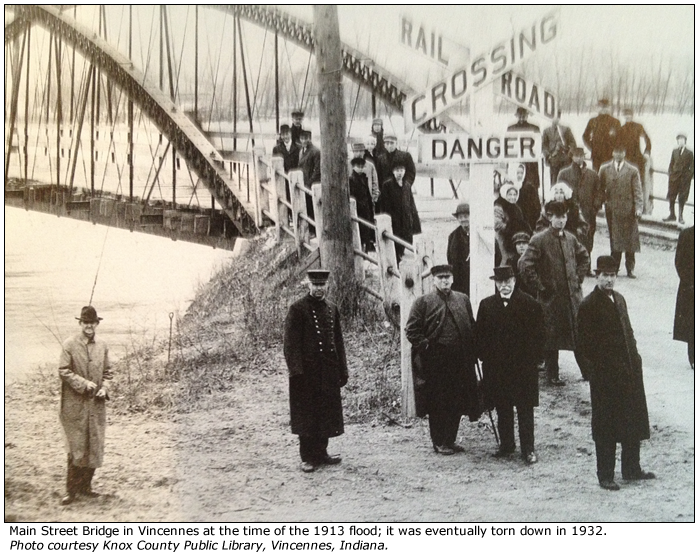

The Wabash continued its dramatic rise over the next few days. By mid-afternoon of March 27, it reached 20.2 feet and Vincennes Mayor James McDowell ordered the Main Street Bridge closed, amid fears that the aged structure could be swept away by the flood waters. Workers at factories and mills were preparing sandbags and moving goods and equipment to higher floors.

Those living on the Illinois lowlands were taking refuge in the city and moving livestock to higher ground.

All were waiting to see how high the river would come.

Wabash Reaches Record Crest at Vincennes - Part 2

On March 28, 1913, as rivers continued their rise during that year’s record-breaking Midwest floods, Knox County residents learned of a horrific flood-related accident that had occurred just east of Wheatland in Daviess County late the previous evening. That night, a work train on the B. & O. S.W. Railroad was traversing a trestle over a deep hole known as Blue Hole. Blue Hole had been carved out during the flood of 1875. When the train, pulling three cars, was on the trestle, the timbers gave way sending the locomotive and tender into the deep, swirling flood waters. Four trainmen perished in the accident, their bodies not recovered for weeks. The Blue Hole story has endured for a century; passed down through the years as a tragic part of area history.

There was little time for local people to dwell on the Blue Hole tragedy. The city of Vincennes remained in a very precarious position. March 28 newspaper headlines trumpeted the news that the flood record had been broken. The river stage at Vincennes at 3:00 p.m. that day was 24 feet, which did surpass the 1898 record of 23.1 feet.

There was still uncertainty as to how high the river would go. The Vincennes Commercial, in a bold headline that same day, gave the dire prediction that it could reach the 26 or 27 foot stage (it would not go anywhere near that level). Levees were rapidly being built along First Street to protect the city, with hundreds engaged in that task. As the Vincennes Capital reported: “…the river front was almost alive with people who are either sight-seers or working at levee building.” Local contractor P.W. Lenahan, along with Charles Dreiman, had teams hauling dirt to build a levee at Jefferson Avenue.

Levee breaks occurred both north and south of the city. There were breaks in the levee near Russellville. Train service in and out of the city was sporadic at best.

Residents of the Oklahoma district on the north end suffered the most. That part of the city was said to have the appearance of “a great lake.” Almost the entire area north of Lyndale Avenue was underwater. About 150 people were rescued by wagon or boat, most of them transported to the Knox County Jail at 8th and Broadway Streets, (some to various homes around town) where they were given quarters on the second and third floors. They were cared for by Knox County Sheriff Adolph Kruse and other relief workers. Sheriff Kruse purchased a supply of bologna to feed them. Chickens, dogs, and other animals were also saved.

By March 29, the city was accurately described as being virtually an island, with the river then on a stand at 24 feet. The Wabash was seven miles wide.

That morning, there was a break in the Brevoort Levee, flooding portions of the south end of town, including parts of the city cemeteries. Both Blackford Window Glass Company at 5th and Willow Streets and the Empire Paper Company at 4th and Willow, were forced to close.

The city was without water for a short time and both electric companies had to briefly discontinue service. The natural gas supply was also disrupted.

The lowlands continued to get the worst of it. Levees on the Illinois side of the river broke, sending water pouring into Lawrence County. Westport was under several feet of water. Boats were sent out to bring in flood refugees. Farmers lost countless head of livestock. The Capital said that the approach to the Main Street Bridge on the Illinois side “…resembles a county fair with horses, cows, hogs, chickens and ducks literally covering it.” Hundreds of wild rabbits took refuge and were captured on the levees.

Of course, the White River was also reaching record levels, inundating thousands of acres of Knox County farm land. Late on March 27, the river at Decker had passed the 27 foot stage.

While Vincennes came through the flood without the devastating losses experience by other Midwest communities, relief work in the city and rescue work out in the county continued.

NOTE: Although newspaper accounts from the time indicate that the flood crest came at Vincennes March 28 at 24 feet, other sources put it several inches higher.

Flood Waters Recede; Relief Work Continues - Part 3

Sunday, March 30, 1913, was a clear pleasant day at Vincennes, although the city remained surrounded by water from the record-breaking flood of that month, after a week of uncertainty and ominous warnings, the Wabash had crested at 24 feet or above and begun to recede, and the danger of the city being further inundated had passed.

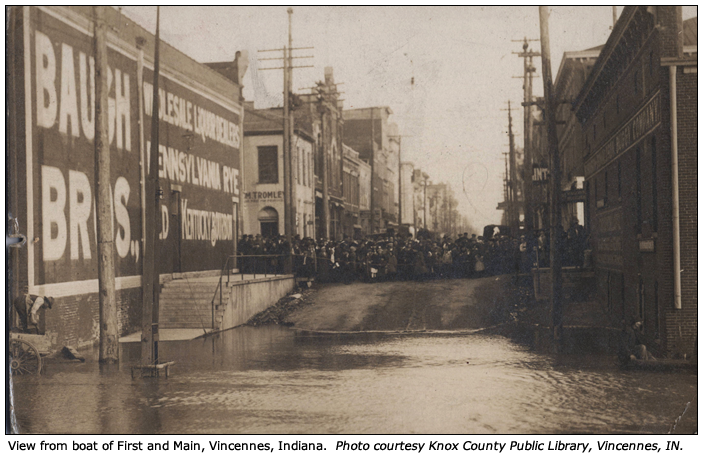

That Sunday saw thousands of residents out along the riverfront and other flooded areas, to view the dramatic scene. The Knox County Courthouse was opened, so that people could go to the upper floors, and even the tower, and get a real “bird’s eye view” of flooded areas.

Almost everyone had their cameras out to document the history-making flood. So much film had been sold that there was no more to be found locally. As the Commercial reported on Tuesday, April 1: “It was stated Monday that the local photographers are crowded with orders to develop kodak films, one firm having over a thousand films to develop, which means that the city will not be lacking in a photographic record of the greatest flood the Wabash valley has ever experienced.”

On Sunday, some people even observed the tradition of strolling the downtown streets in their fine Easter attire, something they had been unable to do a week earlier on what had been a rainy Easter Sunday.

Sightseeing aside, the work of aiding flood victims began in earnest that day, with an afternoon meeting called by the mayor at city hall to organize systematic flood relief. A fund was started to assist with this effort. By April 1, over $3,000 had been donated.

The county jail, at 8th and Broadway Streets, remained the center for relief work, where supplies were stored and people came for aid. The jail was described as resembling a commissary, the halls stacked with shoes, clothing, and food.

Some flood refugees came from out in the countryside. Boats went out as far as the “Neck” in Decker Township, either performing rescues or delivering medicine and provisions to stranded farm families. Large gasoline boats the Mohawk and the Roamer were used in some areas. On March 30, the draw of the Main Street Bridge was opened for these boats to pass through.

Livestock was also rescued. In some rural areas, horses were found standing in deep water.

Although the railroads had sustained untold damage from washouts and would require enormous amounts of repair work, some trains were soon running. On March 31, local mail that had accumulated at the post office was sent out and mail and out-of-town newspapers began arriving. Some mail was brought in by boat. On April 2, over 40 bags of mail were delivered, overwhelming the post office.

The river continued its drop, receding to 21 feet or below by April 1. There was still much suffering in rural areas. The hardships endured were illustrated by a report in the April 4 edition of the Vincennes Sun. The paper told of a situation south of the city on property owned by William Brevoort. There, on a small piece of land that was above the floodwaters, 84 people, all members of tenant families, had taken refuge in four shacks. On that same bit of land were 57 horses and mules, 350 head of cattle, and 400 hogs.

Cleanup from the 1913 flood would continue for weeks, but, overall, the city was very fortunate compared to the destruction visited upon other Midwest cities.

During other floods in the first half of the 20th century, the level of the Wabash River would far exceed the 1913 crest. The years 1930, 1943, and 1950 all greatly surpassed the 1913 mark. In later years, better means of flood control helped protect the city.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Flood Protection Measures

Four Corps of Engineers reservoirs (JE Roush, Salamonie, Mississinewa and Cecil M. Harden) provide combined flood control benefits for about 16-17% of the drainage area upstream of Vincennes, Indiana. Local levees, especially on the Illinois side, provide flood protection for some but not all floods.

To update information about the March 1913 flood at Vincennes, Indiana, contact Al Shipe by e-mail al.shipe@noaa.gov.