The Great Flood of 1913

100 Years Later

Community Profiles: Shelbyville, Indiana

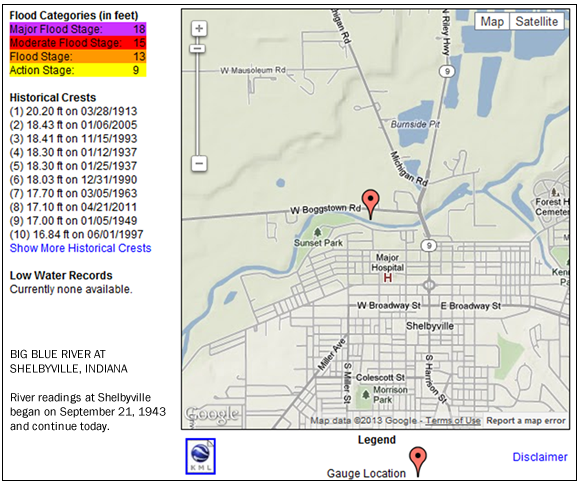

| River: | Big Blue |

| Storm Total Rainfall: | 8" estimated |

| Known Fatalities: | None |

Timeline

"Shelbyville Indiana Flood of 1913" written by Ron Hamilton, Shelby County Indiana Historian

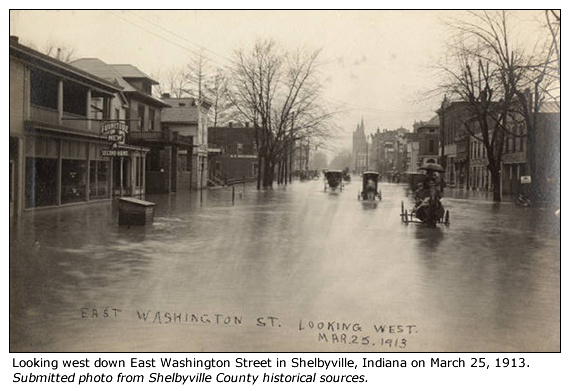

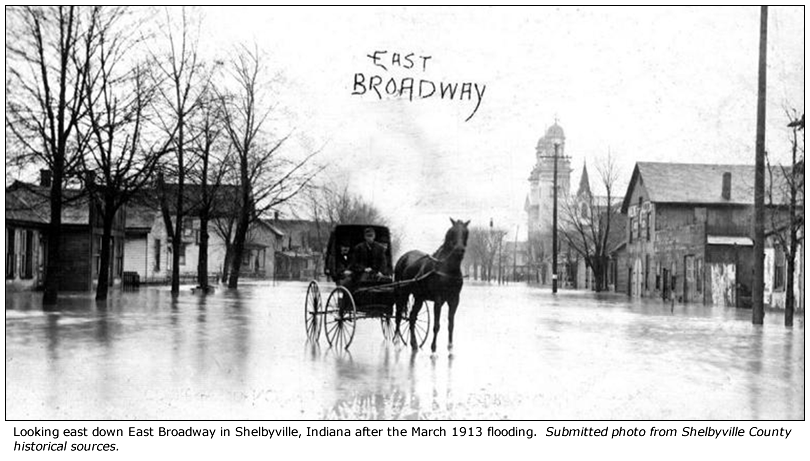

Can you imagine rowing a boat past the Shelbyville Post Office on East Washington Street, or rafting in front of the St. Joseph Catholic Church on East Broadway Street? Town residents did just that on March 25, 1913. Shelbyville and Shelby County has never seen anything to match the catastrophic deluge that hit the area in the spring of 1913. It was a flood of Biblical proportions and caused extensive damage.

According to newspaper accounts of the time, the year started out wet as over six inches of rain fell on frozen ground in January. During March, several inches of snow and over ten inches of soaking rains fell on saturated farm fields and emptied into streams already gorged to capacity. Suddenly, at 2:00 in the morning on the 25th of March, rain started falling in continuous sheets that some compared to a waterspout. Big Blue and Little Blue rivers rose dramatically and shrill alarms from the local fire station and water plant wailed the rest of the night to warn city residents of the impending calamity.

Before daybreak, hundreds of citizens formed work gangs and toted sand bags to the North Harrison Street bridge and levee. These folks were passed by men, women, and children coming into town from the opposite direction, carrying their possessions to the receding high ground in the center of town.

Before daybreak, hundreds of citizens formed work gangs and toted sand bags to the North Harrison Street bridge and levee. These folks were passed by men, women, and children coming into town from the opposite direction, carrying their possessions to the receding high ground in the center of town.

Impacts

All normal activity in town stopped that morning. Over a fifth of the town’s residents were suddenly homeless and many wandered the city aimlessly in stunned disbelief. Men, horses, wagons, and carts were commandeered to help strengthen the levees. By midmorning, the rising waters from Big Blue and Little Blue rivers had reached the first alley east of the Public Square. The city was flooded east of Pike Street, current flowed across South Harrison Street at Locust, and Vine Street was under three feet of muddy water.

Pressure from the water blew off manhole covers throughout the town. Raging torrents carried homes and outbuildings from their foundations. A few miles west of Shelbyville, the Big Blue River grew to a mile wide. The town lost water, gas, electricity, and telephone service. The wagon bridge, railroad trestle, and levee on the north side of town all held, but suffered bad structural damage. As night fell, townsfolk were asked to place candles and kerosene lamps in their windows to throw some light on the blackened sidewalks and streets.

A mother and her new-born baby were rescued from a watery grave at the corner of Pennsylvania and Vine streets by the operators of a horse and buggy ambulance. The mother and infant had only just been removed when an entire section of the house was swept from its foundation. One of the ambulance drivers had to stand near the horses to keep debris from collecting and sweeping the animals away.

The aged, sick, infirm, and disabled were heroically removed from their homes and taken to shelters by volunteers. Trains could not enter or leave the town because parts of the railroad tracks were washed out. Shelbyville could get no help from Indianapolis because the state capital had its own flood problems. The mayor of Chicago telegraphed an offer to help Shelbyville, but officials here politely refused and gave assurances that local residents could deal with the disaster.

The outlying county area also suffered enormously. A train wrecked near St. Paul due to washed out tracks, the Lewis Creek bridge was swept away, and 17 culverts were destroyed in Shelby Township alone. Bridges were out throughout the county and barns, livestock, and grain were all turned into floating debris. The iron bridge over Flatrock River at Geneva was demolished and men spent agonizing hours trapped in trees waiting for the waters to subside.

Surprisingly, while the flood caused hundreds of thousands of dollars in damages, it claimed no lives. Over 2,000 homeless residents were given shelter by local churches, lodges, and the City Hall. As so often happens, town citizens pulled together in this time of crisis and many donated hot soup and clothing for the needy. The town council quickly appropriated $1,000 for immediate relief of flood victims.

In the late afternoon of March 25th, some enterprising county residents apparently dynamited the Freeport levee north of town which enabled the raging flood waters to flow freely out on open, flat fields. This relieved the pressure on downstream Big Blue River and waters began to recede in town. Many city residents left the relief centers to return home, only to find their property seriously damaged by mud and floating debris.

A week passed before the first train managed to reach the town and it was a month before the inter-urban made its return. People in the city and county soon went about the business of cleaning over six inches of mud from their homes. They also began the daunting task of mending railroad tracks, streets, roads, and bridges. The epic Flood of 1913 would eventually fade into memory and provide the sort of stories that legends are made of.

Flood Protection Measures

There are no Corps of Engineers flood control reservoirs upstream of Shelbyille. Local levees protected Shelbyville from flood waters. A flood similar or greater than March 1913 is possible today.

To add information about the March 1913 at Shelbyville, e-mail Al Shipe at al.shipe@noaa.gov.