The Great Flood of 1913

100 Years Later

Community Profiles: Dayton, Ohio

| River: | Great Miami |

| Storm Total Rainfall: | ~7.6" (see note below) |

| Known Fatalities: | Approx. 123 |

Timeline

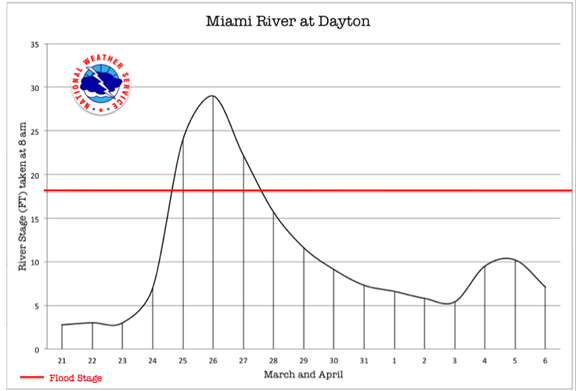

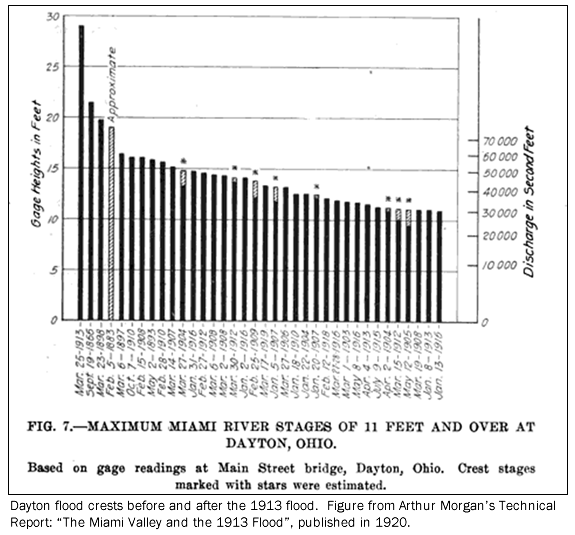

The 29’ crest of the Great Miami River at Dayton on March 26, 1913 had surpassed the previous high water record of 1866 of 21.3’ on the historic river gauge, far surpassing Dayton residents’ knowledge of extreme floods.

The March 1913 storm was an extremely far-reaching catastrophe, resulting in tornadoes in Nebraska and the Gulf Coast states, and hundreds of flood deaths through several states. Even with this widespread devastation, Dayton, Ohio was largely at the epicenter of the storm. With the Miami basin being the most severely impacted river basin affected, Dayton suffered the greatest loss of life and dollar damages, being the largest population center impacted in the basin.

With the heavy rain beginning in the upper Great Miami on March 23rd upstream of Dayton and continuing through the 24th, the river rose fairly slowly the morning of March 24th. By the afternoon, the rate of rise was 6 inches per hour, still not an extreme rise to cause the citizens alarm, or to prepare them for the devastation that was to come. By nightfall, the  river began rising more rapidly, with rises of nearly 2 feet per hour by the morning of the 25th (Miami Conservancy District Report of Chief Engineer 1916 pg 27).

river began rising more rapidly, with rises of nearly 2 feet per hour by the morning of the 25th (Miami Conservancy District Report of Chief Engineer 1916 pg 27).

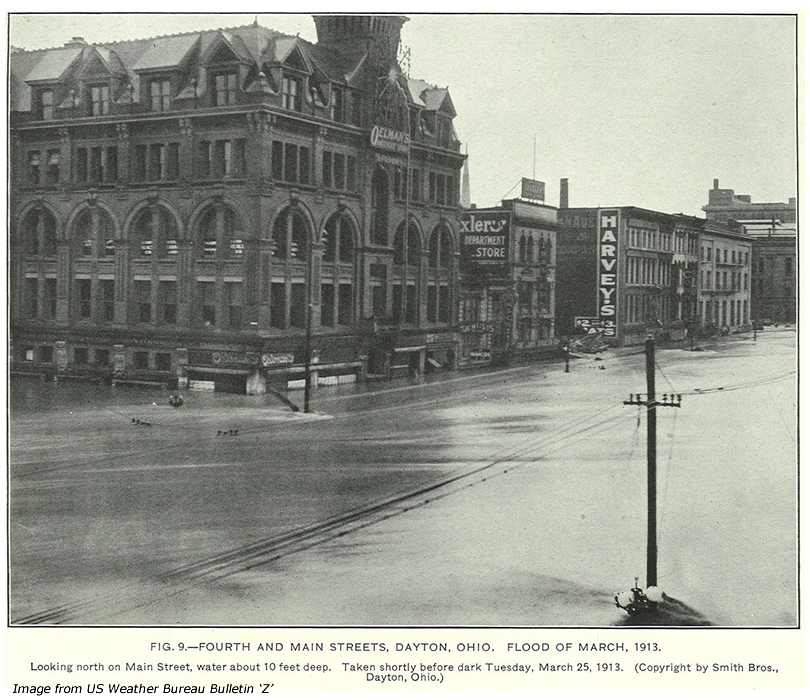

By sunrise on the 25th, a dire situation was realized by most of the city, as three of the city’s levees were overtopped or failed. The business district levees were designed for a flood of 23’, just over 1 foot higher than the previous flood of record in 1866. Between 8 and 9 a.m. on the morning of the 25th, these levees were breached. All levees were easily overtopped as the Great Miami was on its way rapidly to a 29’ crest by the early morning hours of March 26th. Even the 25 feet high levees in north Dayton were overtopped.

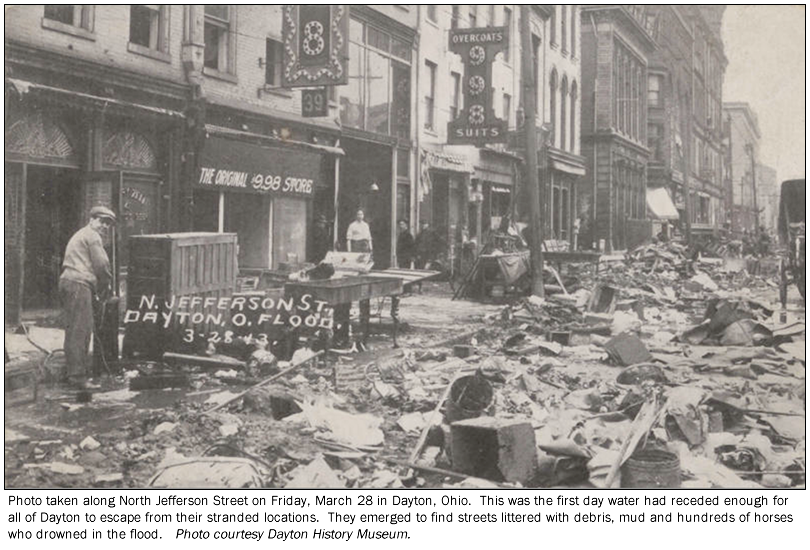

While the Loramie Reservoir in Shelby County and the Lewiston Reservoir in Logan county (now called Indian Lake) were rumored to have failed, neither one experienced a breakage – but rather overtopped – providing little protection to the valley. By 5 p.m. Wednesday, March 26th, the water level had receded, but not significantly enough to improve rescue operations. It wasn’t until Friday the 28th that the river had returned to its banks and most of the city was free of flood waters.

Impacts

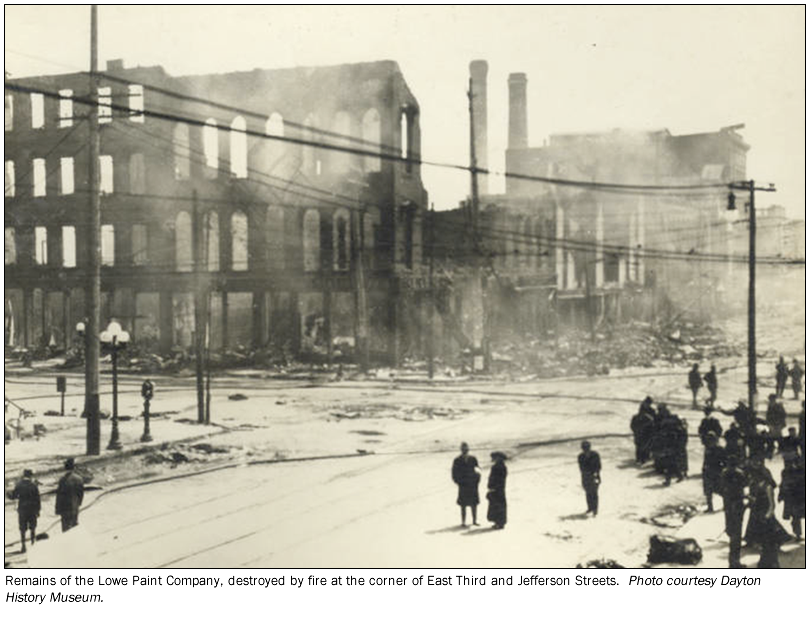

At its crest the river reached a stage of 29 feet resulting in downtown under an average of 10 feet of water and the northern end of town inundated above the second floor of homes. The river just south of town was over a mile wide. In addition to the panic and chaos caused by a rapidly rising river and failing levees, fires broke out through much of the city. Logan Marshall writes of the increased severity of the disaster by fire in Dayton in his 1913 publication, “The True Story of Our National Calamity of Flood, Fire and Tornado”

Crowded in the upper stories of tall office buildings and residences in Dayton, two miles each way from the center of the town, were hundreds of persons whom it was impossible to approach. Hundreds of fires which it was impossible to fight were burning. The rescue boats were unable to get farther from the shore than the throw line would permit. They could not live in the current.

Numerous stories of rescue occurred during this time of incomprehensible tragedy. Hundreds of stranded people were rescued by citizens with rowboats and canoes. Author Trudy Bell writes in her blog on the 1913 disaster of perhaps the most notable hero of the Dayton flood, NCR President John H. Patterson.

In addition to neighbor saving neighbor, there was one citizen who recognized the importance of the data and measurements behind such a massive flood. The U.S. Weather Bureau Local Climatological Summary for the Dayton station depicts the difficulty in maintaining ‘official’ records during a flood of such magnitude:

The Meteorological Bureau for the State of Ohio was established in 1882. In November of that year, Mrs. Edith L. Boyer began a long series of observations at her home, 102 S. Findlay St., Dayton, Ohio. The period of observations at this one location extended for over forty years. The “Boyer Record” was regularly published in Climatological Data through 1923.

The Great Flood on the Miami River in March, 1913, prevented Weather Bureau personnel from reaching the office for a few days. People marooned in the office building in which the Weather Bureau was located evidently drank from the rain gage during their confinement, and the entire record for that period would be open to question if Mrs. Boyer had not sensed their predicament. She continued her observations throughout that trying time. The record of Mrs. Edith L. Boyer as Cooperative Weather Observer deservedly holds a high place among the large, unselfish band of Cooperative Observers who have contributed so much to the Climatological Data of the United States.

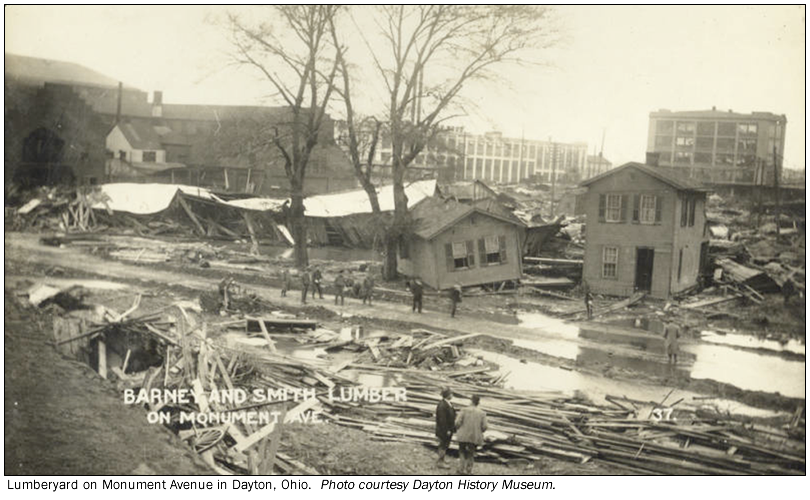

The devastation that remained was one of destroyed passenger and rail bridges, city blocks destroyed by fire, and homes toppled together from the force of 10 to 20 feet of rapidly moving water. Roughly 123 lives were lost in Dayton from the flood.

During the flood at Dayton, the Great Miami River had a discharge of approximately 250,000 cubic feet per second (cfs), though the channel capacity was only for 100,000 cubic feet per second.

Flood Protection Measures

The far-reaching design concept of the early engineers of the Miami Conservancy District was a comprehensive plan to protect much of the Great Miami basin’s population centers. It is a system of five retarding basins without a ‘lake’ or ‘pool’, supplemented by channel improvements and levees through the cities (including Dayton). Each of the retarding dams has permanently open outlets at the base, to allow the normal flow of the river to progress unimpeded at both low and high flow. Such a design eliminates the need for gates or an operator. During periods of high flow, green space and park land was created upstream of the dams to allow the excess flow to flood these undeveloped areas. The center of Dayton is at the confluence of the Mad, the Stillwater and Great Miami Rivers. As a result, four of the five retention dams help protect the city’s population from the ‘official plan flood’, which equates a river flow of the 1913 flood plus an additional 40% of river flow. This level of protection surpasses that of a “1 in 500 chance” flood in any given year (a 0.2% flood), which has been historically known as a ‘500-year’ flood.