The Great Flood of 1913

100 Years Later

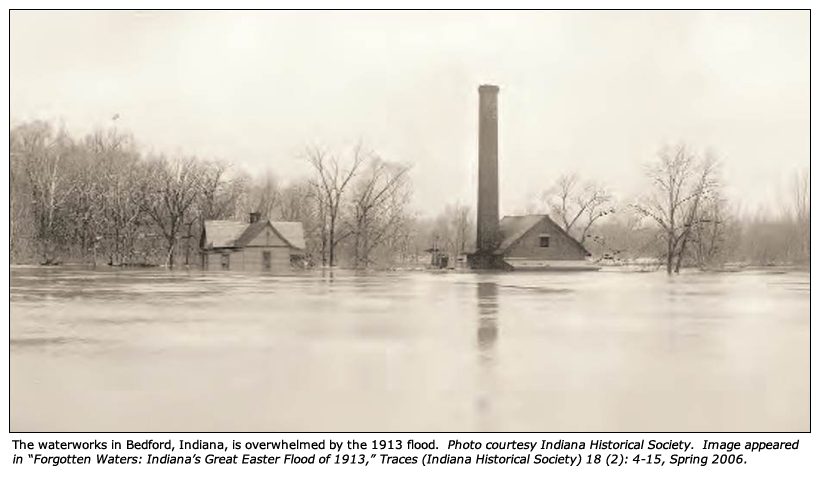

Community Profiles: Bedford, Indiana

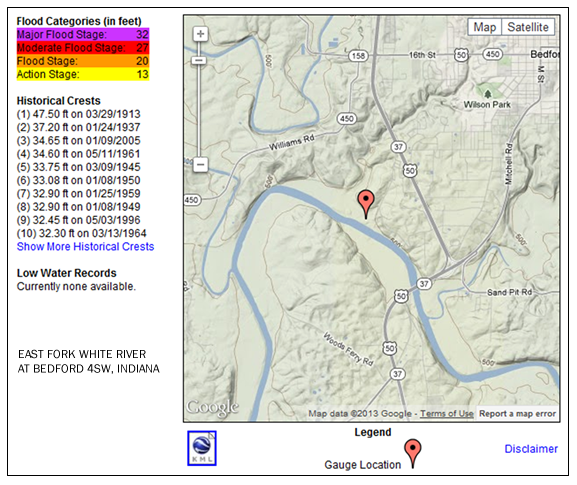

| River: | East Fork White |

| Storm Total Rainfall: | 9" estimated |

| Known Fatalities: |

Article use granted by the Bedford Time-Mail, where it originally appeared on March 24, 2008. Division of the article by Timeline and Impacts is ours.

Timeline

The 'Great Flood' - Lawrence County was under water in March 1913

By Claude Parsons, Special to the Times-Mail

BEDFORD — Ninety-five years ago today, Lawrence and parts of Jackson counties looked somewhat like Orange County did last week after high water invaded roads and neighborhoods.

The “Great Flood” of 1913 occupied front pages of local newspapers more than any other story, for two weeks. Bedford had no communication with the outside world. No local newspapers were delivered for two days.

It all began with a severe storm in Indiana on Monday evening, March 24. Even though the county received no more than four inches of rain that night, by the following day streams and rivers in southern Indiana were rising rapidly.

Winds caused severe damage throughout Bedford — with chimneys toppled, trees uprooted and windows blown in. Sewers were unable to carry off water and numerous basements were filled. Traffic on all roads entering the city was paralyzed by washouts and high water.

And remember, at that time there was no radio or television. Besides that, the storm and flood to follow completely paralyzed all railroad, telegraph and telephone systems in Indiana, Ohio and Illinois.

And remember, at that time there was no radio or television. Besides that, the storm and flood to follow completely paralyzed all railroad, telegraph and telephone systems in Indiana, Ohio and Illinois.

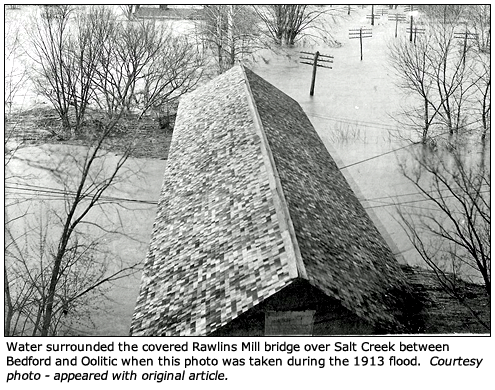

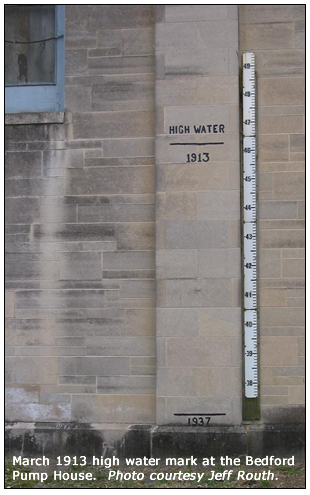

During the next few days, Salt Creek in Lawrence County reportedly rose nearly 10 feet above the high water mark of the record McKinley flood of 1897. It would be at least three weeks before everything would start to get anywhere back to normal.

Impacts

Grocery stores in Bedford reported having large stocks of food on hand to handle any possible famine, but Tunnelton ran low on provisions and it was necessary for five wagons to load up at a local wholesale house and make the delivery.

Mitchell was completely marooned, and for several days no trains of either the Monon or B&O routes could get through. Two houses were washed out at Williams and headed down White River. Topsoil, fences, barns, houses, boats, wharves, river cabins, trees and debris were swept downstream.

Over at Medora in Jackson County, three-fourths of the community was flooded, and most of the 800 residents sought shelter on higher ground. Many remained in second stories of their homes. Luckily, there were no drownings.

Great loss of life during the flood was reported in parts of Indiana, but newspapers said Lawrence County was spared from that tragedy.

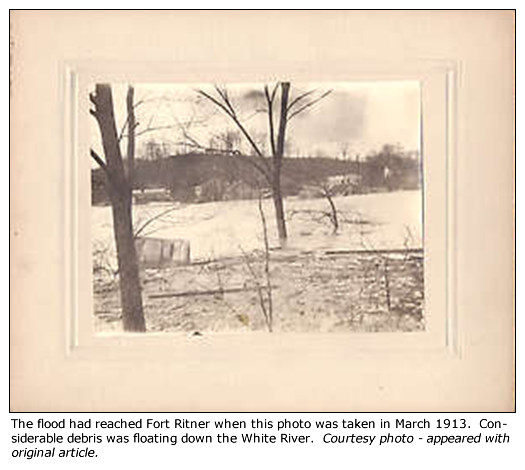

“Practically every resident at Fort Ritner was a heavy loser,” the Bedford Daily Mail reported. “Few had time to get their household goods from their homes before the flood made it impossible.”

In an article appearing in the Times-Mail in 1967, Liberty Root, who had grown up in Fort Ritner, recalled stories of the flood told to her by relatives. From her earliest childhood, stories of the 1913 flood and the Fort Ritner “Crazy House” fascinated her.

The “Crazy House” was a building left in a topsy-turvy condition by the receding flood waters. Hundreds of people flocked to the area, describing difficulties when they attempted to stand or walk inside the structure. The optical illusion was described by many as “exasperating.”

During an interview in 1994, Wilbur Ribelin, then 89, a telegrapher with the B&O Railroad and longtime Fort Ritner resident, recalled his boyhood during the 1913 flood.

“At 4 a.m. one day, the road in front of our house was dry, but by 11 o’clock they were running boats on water over the road,” he said. “The water was up to the doorknob at our house. I remember going by boat on water over a 4-foot-high fence to my grandparents’ home to stay until the water receded.”

A scrapbook belonging to a member of the Ribelin family contained a clipping which stated that the overflow from White River during the 1913 flood “put Fort Ritner in dampness 20 feet deep on Main Street.”

The article added:

“Charley Elmer and two other men paddled around in a boat while a phonograph played ‘Just Floating Down the Wabash.’”

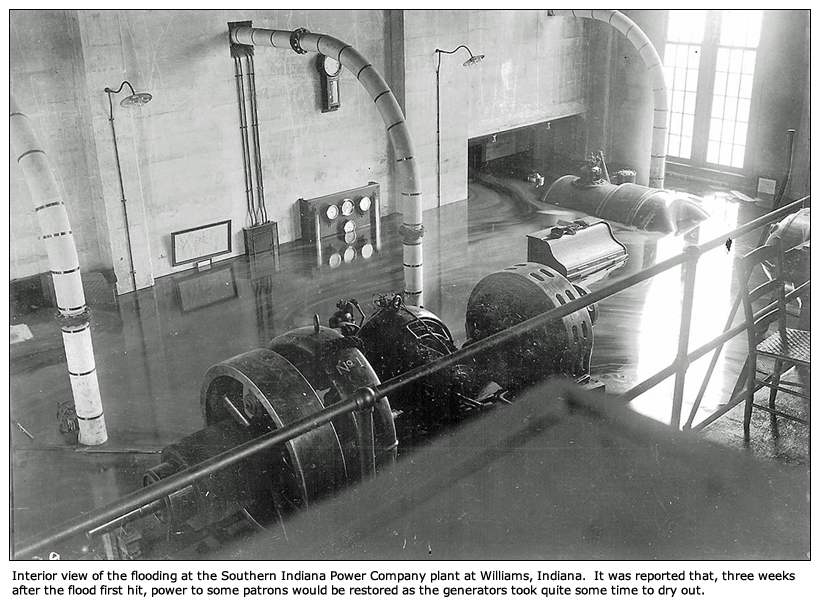

On April 10, 1913, over three weeks after the flood first hit Lawrence County, the Daily Mail reported that the Southern Indiana Power Company, whose plant at Williams had been out of business since the high water, promised power to some of their patrons. The shutdown was caused by water getting over the generators and taking days for them to dry out.

Claude Parsons was a former Times-Mail editor and a frequent contributor to the newspaper.

Flood Protection Measures

Monroe Lake provides a slight reduction in the flood crest at Williams, and a big reduction along Salt Creek in Monroe and Lawrence Counties downstream of the Lake. Salt Creek is primarily flooded by backwater from the East Fork White River.

Monroe Lake, a Corps of Engineers reservoir, provides flood control benefits for about 10% of the drainage area upstream of Williams. There are no Corps of Engineers projects upstream of the Bedford Pump House Gauge. There are no known levees in the local area.

To add or correct information about the March 1913 in the Bedford or Williams areas e-mail Al Shipe at al.shipe@noaa.gov.