The Great Flood of 1913

100 Years Later

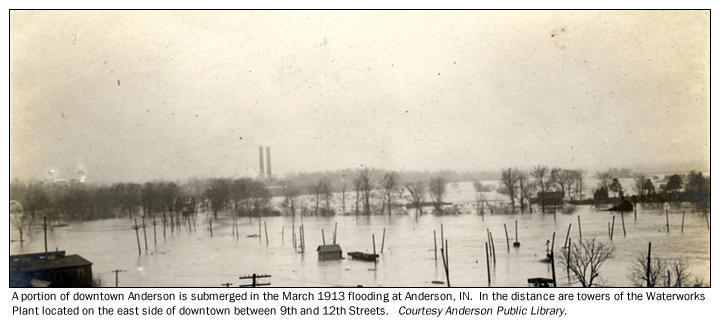

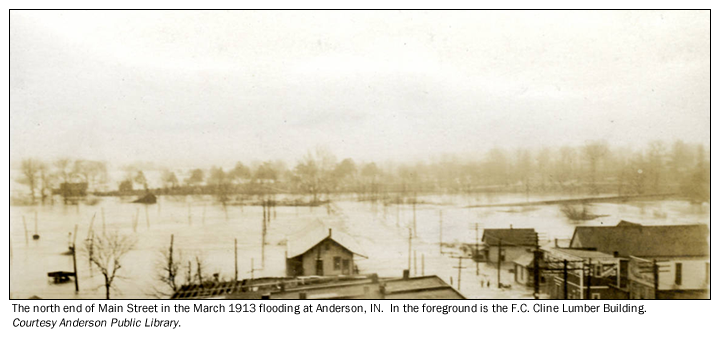

Community Profiles: Anderson, Indiana

| River: | White |

| Storm Total Rainfall: | 6.99" |

| Known Fatalities: |

Timeline

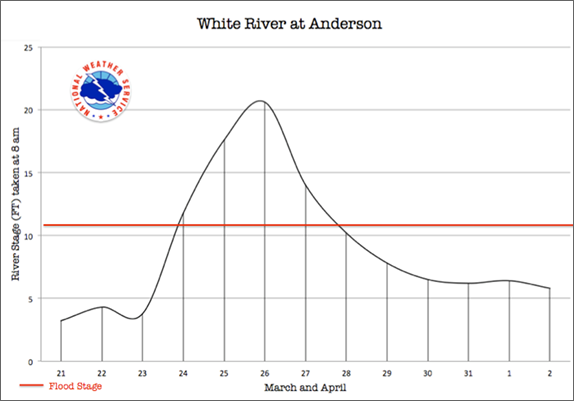

The White River crested at Anderson at a stage of 22.1 feet (higher than shown) on March 25th at the gauge and datum in use in 1913. The March 1913 flood crest at Anderson now translates to 23.6 feet at the Anderson Waterworks Site.

The White River at Anderson was at a typical level for March with a river stage of 3.8 feet on the morning of the 23rd. Heavy rainfall of 6 to 8 inches fell in the White River watershed of Anderson from the afternoon of the 23rd through the afternoon of the 26th. Rain changed to snow late on the 26th, and accumulated 1 to 2 inches by the 27th.

The White River rose rapidly through the morning of the 25th. The river quickly passed flood stage early on the 24th and exceeded all previous records by the morning of the 25th. The river crested later that day at a record 22.1 feet.

Impacts

Flood waters burst through the Anderson levees on the 25th and caused very heavy property damage. Emergency calls began Monday night the 24th, and continued into the 25th. Severe flooding was not limited to Anderson. Rural mail delivery was suspended on all routes out of Anderson because of the raging torrents.

Flood waters burst through the Anderson levees on the 25th and caused very heavy property damage. Emergency calls began Monday night the 24th, and continued into the 25th. Severe flooding was not limited to Anderson. Rural mail delivery was suspended on all routes out of Anderson because of the raging torrents.

Despite severe flooding in the city, The Anderson Daily Bulletin published a two page newspaper on a single sheet of paper on Tuesday afternoon. Headlines included “Hundreds Are Made Homeless”, “River Districts of Anderson Inundated” and “Rescuers Still at Work at Noon”.

What follows are excerpts from The Herald Bulletin online posted June 20, 2009:

In History: 1913 flood cut power, menaced bridges

By Stephen T. Jackson, Madison County Historian

It was Good Friday, March 21, 1913. The Anderson Herald reported a couple planning to marry in the county clerk’s office had to postpone the ceremony because the mother of the prospective bride was unable to get there due to a prevailing storm.

When that storm was over, Madison County had suffered its worst natural disaster on record.

The storm, which was part of a mammoth weather system that wreaked havoc throughout 20 states, drenched our county over the next few days with incessant rains.

Locally, all of the rain water found its way to White River causing a flood that surpassed the previous record. By 3 a.m. Tuesday, March 25, the river was rising at a rate of six inches an hour, and more rain was forecasted. The river finally crested later that day at 22 feet, two feet above the previous high mark set March 27, 1904.

All along the river and back for several blocks everything was under water. Greens Branch overflowed its banks isolating some residents of Hazelwood. Park Place was hit especially hard with 80 homes being flooded with as much as five feet of water in them. Another 50 homes along Greens Branch and about 40 in the extreme northwest part of town were standing in water.

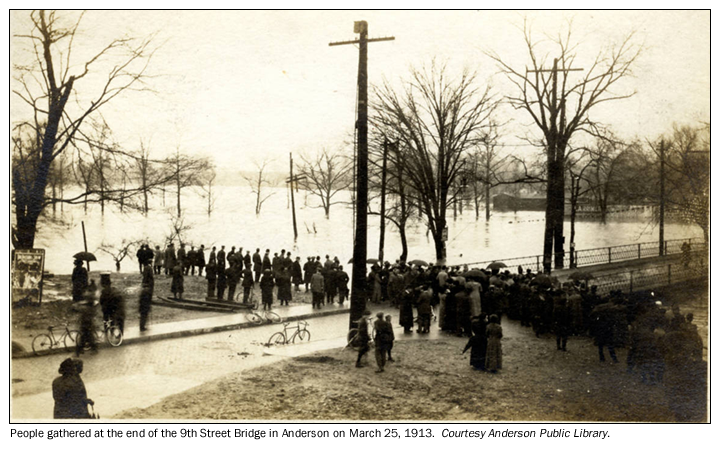

The Ninth and Tenth Street bridges could not be used because the approaches from the east were under water. The Main Street Bridge became unusable after the water going across North Main Street became too deep to go through. One report describes men positioned on the Main Street Bridge using poles to shove down on some of the irregular pieces of flotsam such as outhouses and woodsheds to prevent their lodging against the bridge and creating an obstruction.

For a few additional hours the traction bridge to Park Place was usable for foot traffic, but on the 25th, with the torrent churning against the stringers of the bridge it was too dangerous to cross and Park Place became a world unto itself.

For those who do not recognize the above mentioned bridges, they are no longer in existence. The Ninth Street Bridge has been replaced by the Eighth Street Bridge. The Tenth Street Bridge (also called 12th Street Bridge depending on which way you were going) was demolished and only the supports remain. The Main Street Bridge has been replaced by the Truman Bridge, and the traction bridge is gone; one abutment remains just north of the west end of the Truman Bridge.

On the 25th, Anderson was without water because the overflow of White River flooded the pumping station of the municipal water works. Not only were its citizens without water, the city was without fire protection by water service. Water service was restored late on the 26th.

The city electric light department had to stop its machinery because of the basement being flooded and submerging the condensers. Vast amounts of water were pumped from the basement before the city generators could be restarted the next day. With the loss of light and power for factories, businesses, homes and other concerns, the city was plunged into darkness. But a greater problem was looming.

The bridges over White River were subject to intense pressure created by the rising waters and debris that gathered around their supports. At least three bridges fell victim to the disaster and many others were no doubt weakened and in need of attention.

One of the two last remaining covered bridges in the county was swept away the night of March 25. Both covered bridges spanned White River across separated channels at Perkinsville. These landmarks were thought to be above danger. But during the day on the 25th, water reached the floor of the south bridge. That night the structure let go, sweeping away a relic that had become familiar to every person in that part of the county. Perkinsville was entirely isolated by the water.

Flooding in Park Place began around two o’clock the morning of March 25. Two miles upstream was the Hughel Farm road bridge. It had been built the year before and was short in length with long approaches made by filling each side of the river channel.

Ten foot of backwater was trapped there which caused a part of the long approach to the bridge to give way and let a great volume of water suddenly strike Park Place. The river literally leaped over the 12th Street grade along the east bank near the 12th Street Bridge, causing a current to rush through the west side of Park Place.

A modern day Paul Revere arrived on the scene. Washington Young, a farmer whose land adjoined the Rector Road and bridge grade, saw the rising backwater and knew what would happen to Park Place. He mounted his horse and galloped into Park Place and told of the grade breaking. Soon afterward the water hit Park Place homes, undermining house foundations, tearing furniture out of houses, and creating great crevices in streets.

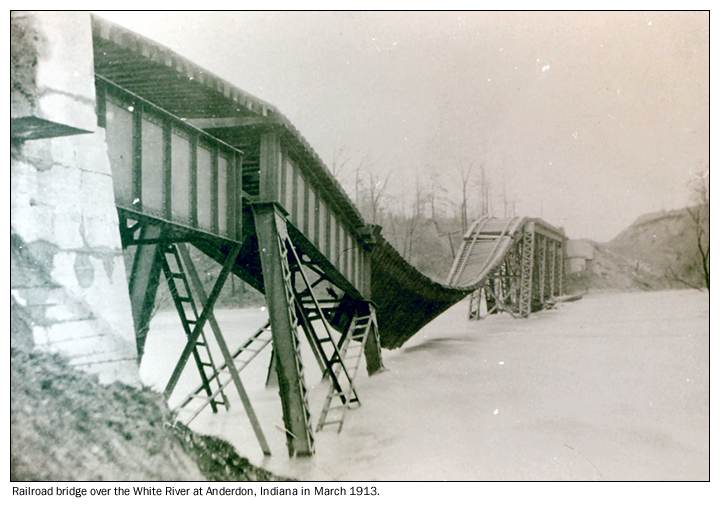

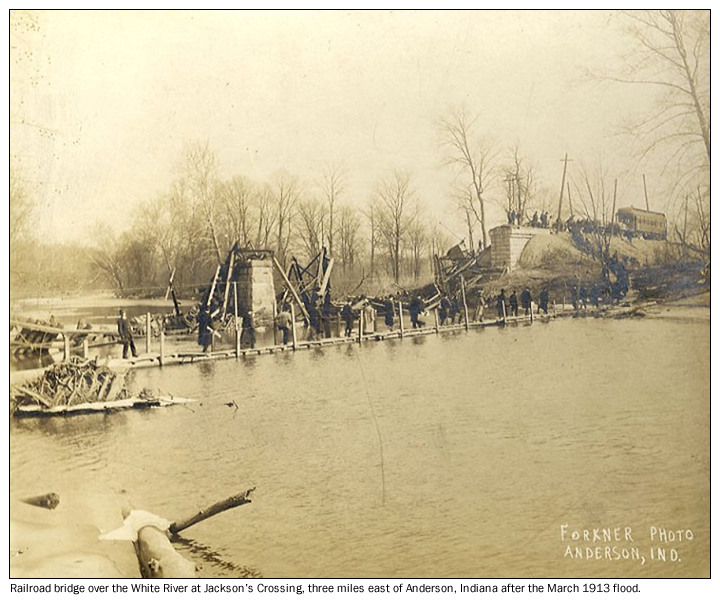

There are two remarkable photographs taken during and after the flood showing bridge damage.

In the first, above, a 200-foot iron truss bridge on the Michigan division of the Big Four Railroad over White River was sagging in the center. The bridge, erected in 1911, held firm while trains passed over during the morning of the 25th. But toward noon the center support began to wash away and finally gave way and dropped the center of the bridge down about 20 feet. A throng of people crowded upon the south end of the structure to view the wreckage of the center of the bridge. The collapsed center lies today in White River where it is mired in the river’s bottom. Below are two photographs taken of the same scene from opposite sides of the river.

The other photograph is of the Union Traction Company’s collapsed bridge over White River at Jackson’s Crossing three miles east of Anderson (below). Repair crews were at the site and working as soon as the water receded. To keep the traction service running, a footbridge was built across the river. Interurban cars would run out from Anderson and meet cars out from Muncie. Passengers would get out and walk across the footbridge to change cars and continue their journey.

If you would like to know more about the flood or view additional photographs of this record-setting disaster, visit the Madison County History Center, 15 W. 11th St., Anderson. The center is open from 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays.

Flood Protection Measures

There are no Corps of Engineers reservoirs upstream of Anderson. Construction of a local levee improvement project protecting much of Anderson is about to begin.

To add information about the March 1913 flood at Anderson, e-mail Al Shipe at al.shipe@noaa.gov.